Rich embroidery traditions across India illustrate living heritage, blending artistry, culture, history, and community resilience.

Embroidery is history, memory, community, and practice bound in thread. Every region, shaped by environment, patronage, and ritual, has developed its own traditions of embroidery over the ages. Here are seven of the myriad embroidery traditions of India, each unique, yet illustrative of how art, history and culture are preserved not only in museums but also in homes and shawls. They remind us that a stitch is never just decoration; it is history, identity, and a living link between past and present.

Phulkari (Punjab)

Phulkari, or “flower work,” is one of Punjab’s most vibrant textile traditions. Its earliest mentions appear in the fifteenth-century ballad Heer Ranjha and in Sikh scripture, showing that it was already part of community identity centuries ago. The craft was worked on khaddar, a coarse, handspun cotton base, with untwisted silk threads known as pat. These threads, sourced from Bengal and Kashmir, glowed with colour, allowing artisans to create bold floral, geometric, and symbolic motifs.

Phulkari has several variations. Bagh Phulkari, where the entire surface is covered with dense embroidery so that the base cloth disappears, is often used for weddings and major celebrations. Chope was worked in red silk on a dark base and traditionally gifted to brides by their maternal relatives. Motifs included peacocks symbolising love, wheat stalks representing prosperity, and diamonds echoing fertility and continuity. Each pattern held meaning and blessings, making Phulkari a living prayer cloth as much as a decorative garment.

Phulkari’s role in Punjabi weddings was central. It formed part of the trousseau, wrapped brides in colour during ceremonies, and reappeared at later family rituals. Importantly, it was a shared craft across Hindu, Sikh, and Muslim households. The tradition was transmitted orally, from mother to daughter, ensuring continuity even in turbulent historical times. Today, Phulkari has found revival in fashion houses and export markets. Dupattas, jackets, and home furnishings carry its spirit to global audiences. NGOs in Punjab now support rural women by linking them with urban buyers, allowing Phulkari to remain both a livelihood and heritage.

Chamba Rumal (Himachal Pradesh)

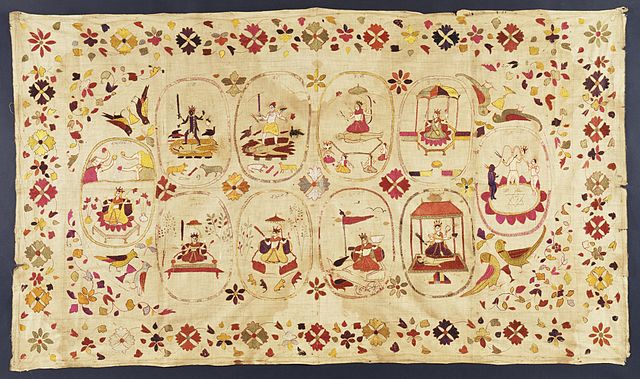

The Chamba Rumal, named after the town of Chamba in Himachal Pradesh, is one of India’s most painterly forms of embroidery. It flourished in the seventeenth century when local rulers patronised artists of the Kangra and Guler schools of miniature painting. These painters collaborated with women embroiderers, transferring painted outlines onto fine muslin or cotton. The embroidery was then filled in with untwisted silk threads using a double satin stitch, ensuring that the image appeared equally clear on both sides of the fabric.

Subjects reflected both courtly life and epic tales. Popular scenes included episodes from the Mahabharata, Krishna dancing with the gopis, or Shiva and Parvati in domestic settings. The miniature style is unmistakable: graceful figures, delicate expressions, and rhythmic compositions rendered in thread. This marriage of painting and embroidery created textiles that were not simply decorative but narrative artworks.

Chamba Rumals held ceremonial and social importance. They were exchanged as gifts during weddings, offered in temple rituals, and valued as tokens of status among the aristocracy. Women of royal households initially led the craft, but local craftswomen soon adopted and sustained it. Today, surviving examples can be found in museums in India and abroad, treasured as fine specimens of Himachali heritage.

Revival efforts have brought renewed attention. Cultural organisations train new generations of embroiderers, emphasising both historical motifs and contemporary uses. Rumals are now framed as artworks, presented in exhibitions, or adapted into smaller textiles for modern homes. Preservation requires careful handling: folding damages the silk threads, so they are stored flat with tissue. For communities in Chamba, the Rumal remains more than embroidery. It is a testament to storytelling, patience, and the ability to turn a square of fabric into a stage for divine drama.

Kutch Embroidery (Gujarat)

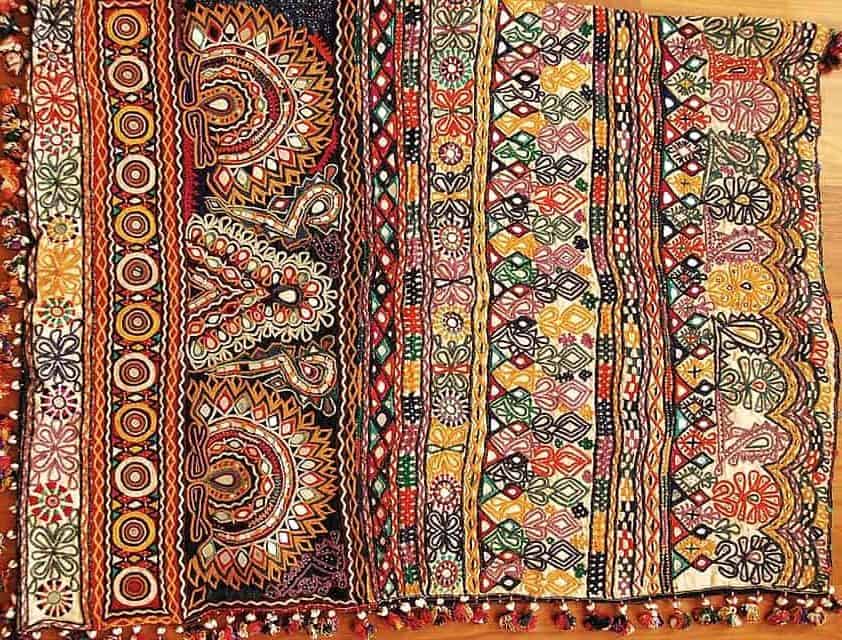

The arid Kutch region of Gujarat bursts into colour through its embroidery traditions. Influenced by nomadic heritage and Central Asian trade, Kutch embroidery thrives on vivid contrasts and intricate embellishment. Artisans work on cotton, wool, or silk bases, using silk and cotton threads to form geometric and floral designs. What sets Kutch apart is its embellishment with mirrors, beads, and cowrie shells. These tiny inserts catch light and create dazzling surfaces, while also carrying spiritual meaning, as mirrors were believed to deflect negative energy.

Kutch embroidery is not monolithic. Distinct styles exist within the region. Suf embroidery features symmetrical geometric patterns built from tiny triangle stitches, executed without pre-drawn outlines. Khaarek is denser, with parallel bands filled with black and white stitches, often used for belts and borders. Paako uses firm, square chain stitches, lending durability to everyday garments. These styles reflect both creativity and adaptation to community needs.

Embroidery plays a vital role in social and domestic life, with blouses, veils, and cushions being carriers of the legacy. Wall hangings and ceremonial garments display the skill of Rabari, Ahir, and other pastoral groups. The work is often taught matrilineally, from mothers to daughters, embedding tradition within family bonds.

In the twentieth century, industrialisation and migration threatened the craft. However, co-operatives and NGOs revived it by linking artisans to national and global buyers. Natural dyes and handspun fabrics are now reintroduced, adding ecological value. Today, Kutch embroidery graces museum exhibitions and fashion runways, yet its heartbeat remains in village homes, where women continue to gather, stitch, and pass on motifs that blend identity with artistry.

Kantha (Bengal & Odisha)

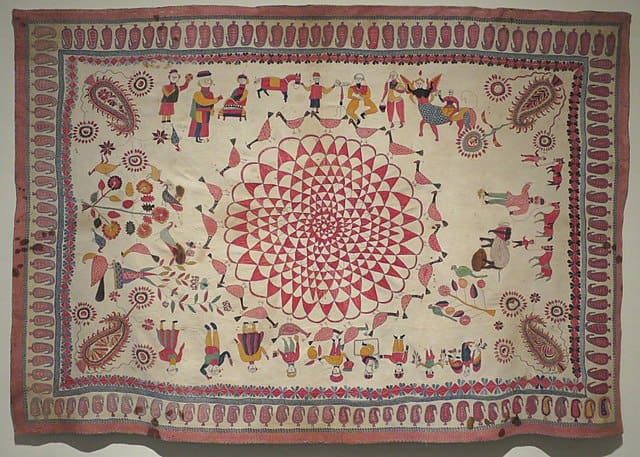

Kantha is one of India’s oldest and most intimate embroidery traditions, practised for centuries in Bengal and Odisha. It emerged from thrift: women recycled worn sarees and dhotis by layering them together and securing them with running stitches. These stitches eventually developed into elaborate motifs, transforming functional quilts into objects of beauty and memory.

Different types of Kantha evolved. Sujni Kantha was made as spreads for ceremonial occasions, often depicting deities, mythical scenes, or village life. Lep Kantha produced thicker wraps for winter, while Durjani Kantha fashioned stitched purses. The stitches formed birds, fish, lotuses, trees of life, and geometric patterns. Some Kanthas acted as narrative cloths, illustrating entire stories or social commentaries. Each piece was unique, bearing the imagination of its maker.

Kantha was not limited to festivals. It was part of daily life: quilts for children, covers for family altars, or dupattas for everyday use. Women stitched in spare hours, turning their lived experiences into motifs. This made Kantha deeply personal, with every line reflecting memory and aspiration. Importantly, it was practised across both Hindu and Muslim communities, showing how creativity flowed beyond boundaries of faith.

Today, Kantha is revived in new forms. Sarees with Kantha borders are fashionable in urban India, while designers export Kantha scarves and stoles worldwide. Craft collectives in Bengal employ thousands of rural women, providing livelihoods. Preservation requires care: Kantha should be folded on different lines periodically and aired regularly to avoid damage. As an art form, Kantha embodies resilience, resourcefulness, and storytelling. Each stitch is both practical and poetic, transforming old cloth into a carrier of cultural identity.

Zardozi (Delhi, Lucknow, Hyderabad, Bhopal)

Zardozi, meaning “sewing with gold,” epitomises opulence. The craft was introduced to India from Persia and found its golden age under the Mughals. It flourished in the ateliers of Delhi, Lucknow, Hyderabad, and Bhopal, where emperors and nawabs demanded ceremonial costumes, wall hangings, and furnishings glittering with metallic splendour.

The technique uses gold and silver threads, often combined with sequins, pearls, and precious stones, embroidered onto rich fabrics such as velvet, satin, and silk. Motifs range from scrolling foliage and paisleys to dense floral sprays, all designed to shimmer in candlelight. Male artisans, known as zardoz, trained for years to perfect their craft, passing it down through generations.

Zardozi suffered a decline during colonial rule when cheaper machine-made imports flooded markets. However, it was revived in the twentieth century with state patronage and later by India’s growing bridal fashion industry. Today, Zardozi adorns lehengas, sarees, sherwanis, and couture gowns. It has also found a niche in accessories such as clutches and shoes.

The craft has economic importance. In cities like Lucknow, thousands of artisans are employed in Zardozi workshops, though they face challenges of fair wages and recognition. Designers have helped raise its profile, but sustaining livelihoods requires continued patronage and ethical practice. Caring for Zardozi is delicate: metal threads tarnish if exposed to moisture or perfume, so garments are wrapped in muslin and stored flat. Despite these demands, Zardozi remains one of India’s most dazzling heritages, a symbol of continuity between Mughal magnificence and modern couture.

Aari Embroidery (Gujarat, Rajasthan, Karnataka, Kashmir)

Aari embroidery is famed for its fluid lines and delicate finish, worked with a hooked needle that produces fine chain stitches. The technique originated during Mughal rule, influenced by Persian embroidery, and spread widely across India. Regions such as Gujarat, Rajasthan, Karnataka, and Kashmir adopted it, each adding local flavour.

The hooked aari needle allows rapid yet precise stitching, ideal for floral vines, paisleys, and scrolling borders. On fine cottons and silks, artisans create flowing motifs that appear drawn rather than sewn. Metallic yarn often enriches designs for weddings and ceremonies, while tone-on-tone work achieves subtle elegance.

Regional variations developed. In Gujarat and Rajasthan, Aari was associated with bridal wear and decorative household items. In Kashmir, Aari merged with crewel embroidery worked in wool, adorning shawls and furnishings. In Karnataka, artisans adapted it to saree borders and blouses, giving southern India its own interpretation.

Aari embroidery continues to thrive because it adapts easily to both couture and mass markets. Bridal blouses, evening jackets, and even cushion covers showcase its versatility. Workshops often divide labour, with artisans specialising in outlining, filling, or finishing, allowing large commissions to be completed on time. Families across generations practise the craft, making it both livelihood and identity.

Care is straightforward yet vital. Aari embroidery must be kept away from sharp jewellery that can snag loops. Ironing is done on the reverse with a pressing cloth. If a thread breaks, it should be secured rather than pulled, as tugging distorts the line. With thoughtful preservation, Aari pieces last decades, proving the strength of a simple tool in the hands of a skilled artisan.

Toda Embroidery (Tamil Nadu, Nilgiri Hills)

Toda embroidery, practised by the Toda tribe of the Nilgiri Hills, is a bold declaration of identity. It uses unbleached white handwoven cotton as the base, embroidered with red and black wool in geometric motifs. From a distance, these designs resemble architectural patterns, while up close they reveal subtle variations that show the human hand at work.

The most iconic garment is the pothkul, a shawl worn both in daily life and at ceremonies. It symbolises clan belonging and social status. Motifs often carry layered meanings linked with fertility, buffalo herding, and sacred dairies, all central to Toda cosmology. Embroidery is primarily practised by women, passed from mother to daughter, ensuring its continuity within community life.

The shawl moves fluidly between ordinary and sacred contexts. It protects from cold in the hills but also enters temple spaces and weddings with solemnity. Tourists and collectors have recently shown interest in Toda embroidery, creating opportunities and challenges. Ethical collaborations are essential to prevent exploitation and to ensure the community retains control over its cultural heritage.

Preservation is practical. Woollen threads require cool hand washing and drying flat. As the shawls age, the white cloth deepens in tone and the wool softens, creating heirlooms of both warmth and cultural pride. For the Toda tribe, embroidery is not just decoration. It is a living language of belonging, ritual, and continuity, stitched into every fold of their shawls.

Chikankari (Lucknow, Uttar Pradesh)

Chikankari is among the most delicate and elegant embroidery traditions of India, rooted in the city of Lucknow. Its origins are often traced to the Mughal period, with stories crediting Empress Nur Jahan for popularising the art in the seventeenth century. The technique is defined by its subtlety: white thread embroidered on fine white cotton or muslin creates a whisper-soft effect that feels both ethereal and timeless.

The craft involves more than thirty distinct stitches, ranging from simple running stitches to complex forms such as jali work, where the fabric is delicately manipulated to create a lace-like effect. Motifs draw heavily from nature: paisleys, creepers, flowers, and foliage dominate, reflecting Mughal aesthetics and the refinement of Lucknow’s artistic culture. Traditionally worked on muslin, today Chikankari also adorns fabrics such as silk, georgette, chiffon, and organza, giving it contemporary versatility.

Historically, Chikankari garments were prized as symbols of elegance and status, worn by nobility and courtiers. Over time, it became an integral part of daily wear for both men and women in Lucknow, most famously in the form of the kurta.

The embroidery is sustained largely by women artisans in and around Lucknow, many of whom rely on it for livelihood. Cooperative societies and designers have played a role in revitalising the tradition, bringing it to global audiences while safeguarding its authenticity. Caring for Chikankari requires gentleness: light hand washing, careful ironing, and storage away from harsh light to maintain its signature softness.

Read More: Latest

2 Comments