Sacred Fabric traditions of Paint, dye and thread interwoven with devotion, memory and culture

Across India, textiles can be more than just a piece of cloth; they are scripture, shrine, and social memory threaded into fabric. In deserts and river plains, temple towns and mountain monasteries, artists, weavers, singers and tailors turn cotton, silk and brocade into living embodiments of faith. Every bit of paint, dye and thread carries histories of devotion, caste, patronage, migration and resilience.

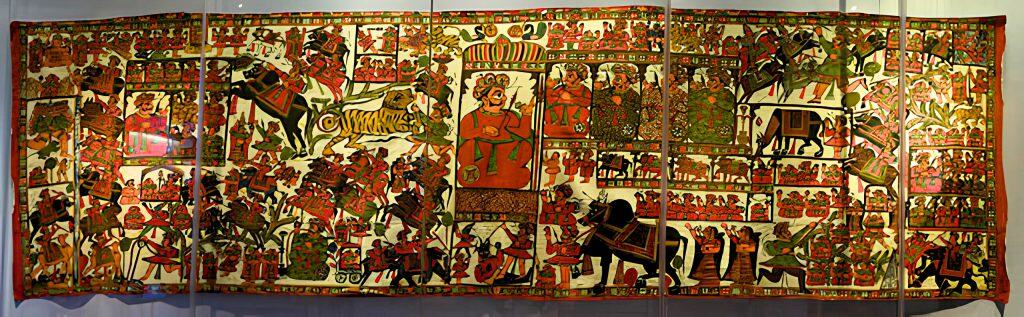

Phad: Painting Devotion

Deep in the arid Thar Desert fringes of Bhilwara and Salumbar, the bhopa–bhopi families of the Nayak and Maru castes continue a 400 year-old scroll tradition that turns cloth into a travelling temple. Artisans like the famed Kalyan Joshi prepare each phad on coarse cotton or canvas, priming it with chalk and gum before painting with natural pigments: geru for earthy reds, safed for luminous whites, lampblack for night skies.

A single 15-by-5-foot Pabuji phad takes up to 20 days. Socially, these scrolls preserve pastoral caste histories: Pabuji as the protector of herds, Devnarayan as a Bhil warrior-hero whose stories once moved with monsoon migrations of communities. As village audiences shrink, artists drift toward Jaipur craft fairs where painters like Shyam Sundar Joshi sell mini-phads to urban buyers, but some bhopa lineages still raise full scrolls nightly, singing for grain or cash, invoking fertility and rain in climate-stressed farmlands.

Mata ni Pachedi: Shrines on Cloth

In Ahmedabad’s Pirana and the Vaghri (Devipujak) hamlets that ring the city, Mata ni Pachedi comes to be in open courtyards where lengths of cotton or silk are stretched out, through the hands of hereditary kalaks from the Parmar, Solanki and Chitara families. This striking textile tradition, essentially a portable temple, was shaped by centuries of exclusion, when Vaghri communities were denied entry into formal shrines. In response, they painted their own sacred spaces on cloth.

Men render the first outlines with carved wooden blocks or bamboo kalams dipped in natural dyes, while women bring the scenes to life with dense detailing of lotuses, devotees, guardian animals and the many fierce village goddesses who anchor their faith. A single pachedi can take 10 to 15 days, and experienced artists may even employ more than 40 blocks to complete one. The heart of the tradition still beats in Pirana during festivals: smoke drifting around a stretched pachedi, drums echoing, goats circling the central Mata as elders recount histories of resilience woven into every panel. For travellers, it is an arresting blend of graphic beauty and a community’s centuries-old claim to spiritual dignity.

Srikalahasti Kalamkari: A Pen of Faith

In the pilgrimage town of Srikalahasti, near Tirupati, one of South India’s most atmospheric sacred textile traditions comes alive in ink, dye and devotion. Srikalahasti Kalamkari is entirely hand-painted, created with nothing more than a bamboo or date-palm kalam and a palette of natural dyes painstakingly built through cycles of mordanting, resist and dye baths. Artisans sketch fluid outlines directly onto cotton and gradually deepen them into rich reds, indigos and blacks, allowing mythic scenes to unfold with an ease and intimacy impossible in other Kalamkari centres.

While coastal Machilipatnam Kalamkari relies on carved wooden blocks and patterned repeats suited to yardage and sarees, Srikalahasti’s freehand technique is designed for narrative expression, enabling long, continuous story cycles from the epics and the Puranas to stretch across a single cloth like a sacred mural.

Historically, these pieces served as sanctum backdrops, festival screens and chariot hangings, transforming temple spaces into immersive panoramas of deities, sages and cosmic landscapes. Practised since at least the late medieval period and traditionally associated with the Balija community, the craft now carries Geographical Indication status for its distinct technique and ritual depth.

Poetry in Ikkats

In the weaving corridors of Nuapatna and Maniabandha, devotion is woven thread by thread into Khandua Pata. Jayadeva’s 12th-century Gita Govinda transforms ikath into scripture. Weaver families practise a single-ikat technique so intricate that verses appear crisp on silk the moment the cloth comes off the loom. Mulberry silk is tied, dyed, and re-tied in painstaking cycles, the text and motifs mapped mentally rather than sketched, a skill passed down through temple-assigned lineages.

Artisans like Sankar Sabat still produce temple-specific Khandua pattas, 36-by-48-inch cloths dyed in the chariot colours of Ratha Yatra, over 20 days, observing ritual fasts before weaving cloth destined to touch the bodies of Jagannath, Balabhadra and Subhadra. Temple records such as the Madala Panji recall how Gajapati kings granted entire villages to sustain this ritual economy, sanctifying Khandua as the “skin” of the gods.

In the same lanes, however, secular variants bloom: sarees with borders echoing temple carvings, pallus quoting fragments of Gita Govinda, and export pieces that reinterpret the traditional palette. Women weavers now run cooperatives balancing temple orders with global demand, even as mechanisation and youth migration thin the ranks. No more than 200 temple-linked looms survive today, a fraction of their historic strength.

Walk through Nuapatna’s alleys, and you’ll hear the rhythmic thrum of looms under banyan trees as weavers recount tales of royal audits, shifting markets and GI-tag revivals. In their hands, a bolt of silk becomes a bridge between devotion, livelihood and centuries-old state patronage.

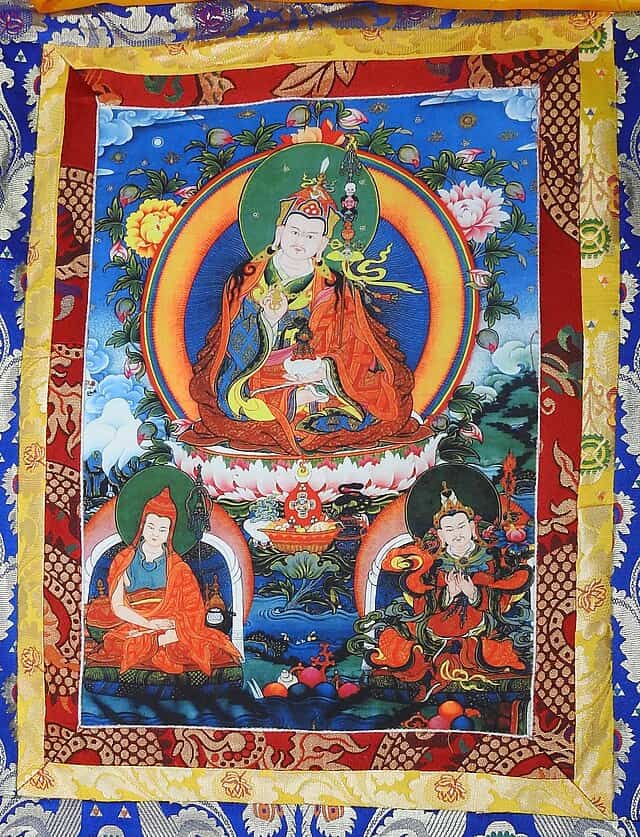

Thangkas: Stitching the Divine

In the high monasteries of Ladakh, Himachal Pradesh, Sikkim and Arunachal Pradesh, textile-making becomes a form of devotion. During long Himalayan winters, groups of monastery-trained tailors, nuns and local women create giant appliqué thangkas, spectacular 20-foot cloth banners showing deities such as Padmasambhava or Avalokiteshvara. Using a technique called tshem drub, they layer rich brocades, silks and handspun wool, outlining faces and ornaments with delicate silk thread.

Inside the monastery halls, painters known as lharipas work on traditional thangkas made with ground minerals like lapis, malachite and ochre, and sometimes even real gold. These paintings act as portable teaching tools, carried on pilgrimage routes or unrolled during festivals. A single appliqué banner can take half a year to complete before it is blessed with chants and displayed only once annually, turning courtyards or rocky hillsides into breathtaking open-air shrines.

These traditions grew around monastery life, hereditary painters in Ladakh, women’s stitching groups in Tawang, and carefully trained workshops in Sikkim. Today, tourism brings both support and challenges: souvenir stalls sell simpler prints, and monasteries carefully decide which sacred images can be photographed or sold.

Visit Korzok Gompa during the Guru Rinpoche cham festival, and you might see a century-old appliqué thangka unfurling in the mountain wind, a moving reminder of how Himalayan communities preserve their spiritual heritage through cloth, colour and extraordinary patience.

Looking Ahead

Preserving these sacred cloth traditions grows harder each year as patronage shifts, younger generations leave for other work, and cheaper substitutes crowd the market. Yet their future is not lost; these inherited worlds endure with every stitch and stroke of the pen. Their survival will depend on thoughtful support from communities, travellers, institutions and collectors, who recognise that such cultural wealth is an irreplaceable record of India’s collective history.

Read More: Latest