Embarking on a gastronomical journey with Flavours of India through India’s iconic regions, exploring bold spices, soulful stories, and timeless tastes.

India’s culinary identity is deeper than spices. It is a reflection of land, climate, society, and tradition. Each region brings its own rhythm to the plate, shaped by geography, faith, and seasonal produce. These time-honoured customs turn daily meals into moments of remembrance and celebration.

The sweet and salty balance of Gujarati cuisine, the sharp mustard notes of Bengali food, the coconut-kissed comfort of Kerala food, and the smoky, wild essence of Northeast Indian food all reveal new shades of India’s soul.

In this country, food is never merely consumed. It is inherited. Passed through generations, shaped by monsoons and rituals, it speaks of what people value, protect, and celebrate. A bowl of fermented rice, a festive thali, and a dish stirred in silence all carry the Flavours of India in their truest form.

Gujarat – Sweet, Tangy & Vegetarian Elegance

Gujarati cuisine is a lesson in balance and inventiveness. Deeply influenced by Jain and Vaishnav traditions, it remains largely vegetarian. It reflects a philosophy rooted in non-violence, minimalism, and seasonal eating.

One of the key traits of Gujarati cuisine is its use of jaggery and sugar. These sweet elements balance sour and spicy flavours. Tamarind, mustard seeds, and green chillies often appear, but the gentle sweetness gives Gujarati dishes their unique identity.

The classic Gujarati thali offers a remarkable variety. It includes rice, rotlis, dal, kadhi, two-three vegetable preparations (shaak), chutney, pickle, a sweet, and a glass of chaas. This generous combination captures the Flavours of India on a single plate.

Snacks like dhokla and khandvi are well-known beyond Gujarat. Dhokla is a steamed, spongy cake made with gram flour and fermented batter, garnished with mustard seeds and coriander. Khandvi, made using spiced besan rolled into thin layers, is topped with coconut and carries a silky texture.

Thepla, made using fenugreek leaves and wheat flour, is a travel favourite in Gujarati cuisine. Its earthy, mildly spiced taste and long shelf life make it a kitchen staple.

Teatime in Gujarat is close to sacred. In cities like Ahmedabad and Surat, streets bustle with jalebi-fafda vendors. Gathiya, bhakarwadi, and sev also shine during this hour, part of the Farsan tradition that defines Gujarati food culture.

Seasonal dishes reflect the deep bond between soil and the kitchen. Aamras with steaming puris in summer is refreshing. Winter invites undhiyu, a medley of root vegetables, beans, brinjals, and fenugreek dumplings, slow-cooked in earthen pots buried underground. Rich and rustic, it speaks the language of Gujarat’s heartland.

Beyond the thali, you’ll discover treasures like ponk, made using tender jowar grains and served with sev and lemon. Adadiya pak, a nourishing sweet using black gram flour and dry fruits, and muthiya, steamed fenugreek dumplings, often enrich vegetable curries.

Street food reveals another vibrant side of Gujarati cuisine. Locho, a spicy steamed delicacy, sev khaman, masala khakhras, and sukhdi—a jaggery, wheat flour, and ghee fudge—bring daily life and storytelling into each bite.

If you are in a city canteen a village courtyard, Gujarati meals reflect generosity, comfort, and a deep love for flavour. This is where the Flavours of India come alive in every bite—rooted in tradition, shared in joy.

Bengal – Where Fish, Sweets, and Mustard Rule

Bengali food is a celebration of rivers, rituals, and refined taste. It combines the rustic charm of village kitchens with the elegance of royal feasts. Every meal in Bengal flows like poetry, simple, expressive, delicate, and bold.

Fish forms the heart of Bengali cuisine. The region’s rivers, especially the Ganges and Padma, offer a wide variety. Among them, hilsa ilish reigns supreme. It’s steamed in mustard, cooked with eggplant, and paired with pulao. For Bengalis, ilish is not merely a dish, it is emotion.

Daily meals showcase humble stars. Macher jhol, a light fish curry, and moong dal with fish head are staples that reflect the soul of Bengali food. These dishes use basic ingredients and deliver deep, comforting flavour.

Vegetarian preparations hold a place of pride. Cholar dal, enriched with ghee and coconut, often appears beside luchis during festive occasions. Aloo posto, made using potatoes and poppy seed paste, is subtle yet impossible to resist. Shukto, a bittersweet mix of vegetables in milk gravy, brings calm grace to a traditional Bengali lunch.

Kolkata’s street food offers a vibrant, colonial-tinted contrast. On its busy pavements, you’ll find cutlets, rolls, and fritters inspired by the British Raj and reimagined with Bengali flair. The kabiraji cutlet, wrapped in a crispy egg-net, still stands as a favourite in old cafés and cabins.

At the Indian Coffee House, where thinkers and writers gather, you’ll still find those timeless cutlets and endless cups of coffee. This mix of memory and flavour is part of the wider Flavours of India that Bengal contributes with pride.

Sweetness marks the finale but also the essence of Bengali food. Sweets are not additions. They are showpieces. Sandesh, often flavoured with nolen gur (date palm jaggery), showcases the craftsmanship of Bengali sweet-makers. Rasgulla, soft and soaked in syrup, has gained global fame and sparked spirited debates about its roots.

Other beloved classics include mishti doi (sweet yoghurt), cham-cham, payesh (rice pudding), and roshbhora, a rasgulla filled with khoya and dipped in syrup. These are more than desserts. They are edible elegance.

Among rural and working-class households, panta bhat remains a beloved classic. Fermented rice, soaked overnight and served cold with mustard oil, salt, green chillies, and onion, is soothing during the summer heat. Though not often found on restaurant menus, this dish is central to Bengali cuisine.

Food in Bengal moves with rhythm and reverence. Meals are never rushed. Each preparation, served on a zamindar’s brass plate, a terracotta dish, a banana leaf, reflects care and emotion.

This love for balance, between mustard, fish, and sugar, and the strength of culinary memory, places Bengali food among the most treasured Flavours of India.

Kerala – Spices, Seafood, and Soulful Feasts

Kerala food is a fragrant journey through history. This coastal state, known as the “Spice Garden of India,” has shaped global trade for over 3,000 years. Traders from Arabia, Portugal, the Netherlands, and Britain all left their mark, but the core of Kerala cuisine remains deeply local and seasonal.

Coconut is central to Kerala food. It appears as grated flesh, milk, and oil. Alongside rice, it forms the base of most meals. Tamarind, curry leaves, and green chillies balance the sweetness with sharp, zesty notes. Together, they create a rich, layered palate, key to the Flavours in this region.

Breakfast in Kerala is one of the most creative meals. Try puttu, steamed rice flour layered with coconut, paired with spicy kadala curry made of black chickpeas. Appam, the lacy rice pancake, is soft in the centre and crisp at the edges. It pairs beautifully with vegetable and mutton stew, delicately spiced and simmered in coconut milk.

Idiyappam and string hoppers, soak up mild curries. Even the everyday idli-sambar combo gets a Kerala twist with tangy chutneys and drumstick-infused sambar. These staples of Kerala food prove how comforting and nourishing a morning meal can be.

Seafood plays a starring role in Kerala cuisine. Along the Malabar coast, you’ll find fiery prawn curries, often tinged with kokum and raw mango for tang. Fish molee, a dish of fish cooked gently in coconut milk, shows Portuguese influence but remains unmistakably Malayali.

Thalassery biryani, a signature of the Moplah Muslim community, is another gem. It uses short-grain jeerakasala rice and mild spices. Sweet, savoury, and aromatic, it captures the festive side of Kerala cuisine.

Vegetarian fare shines during the grand Onam feast, known as Sadhya. This banana-leaf meal can feature over 24 dishes served in a specific order. Avial, a mix of vegetables in coconut and curd, sits alongside olan (white gourd in coconut milk), erissery (pumpkin-lentil mash), and pachadi (spiced yoghurt). Crisp banana chips, spicy pickles, and cooling payasam complete the feast.

Sadhya isn’t a meal, it’s a ceremony. And it embodies the Flavours of India in their most generous, celebratory form.

Snacks and sweets hold their charm. Pazham pori, which is fried ripe bananas, make for the perfect teatime treat, especially during monsoon showers. Mussel stir-fries, toddy shop specials like spicy tapioca with fish curry, and ada pradhaman (a jaggery-based payasam) are beloved across generations.

Every dish in Kerala food holds a memory. Recipes are passed down across families, especially among the Syrian Christians, Namboothiris, and Moplah Muslims. These communities have kept alive a cuisine that is humble yet complex, familiar yet timeless.

Kerala’s cuisine is deeply rooted in its soil, soaked in history, and shaped by sea winds and monsoon rains. No culinary trail of India is complete without a stop at this spice-laden coast.

Seven Sisters of Northeast India- Wild, Fermented, and Fearlessly Flavoured

North East Indian cuisine offers some of the most unexplored and earthy representations of flavours of India if you want to experience them all. These are foods that have been fermented in bamboo, cooked over a wood fire, and cultivated in the woods. The cuisine of the Seven Sisters states, Arunachal Pradesh, Assam, Manipur, Meghalaya, Mizoram, Nagaland, and Tripura, is based on survival, instinct, and the changing of the seasons.

Arunachal Pradesh – Comfort Food with Tibetan Roots

High altitudes, chill winds, and ancient Tibetan connections shape Arunachal Pradesh’s food. Meals are hearty, not heavy. Rice, millet, and barley form the base, while local herbs, smoked meats, and fermented vegetables add the flavour.

Beyond dishes like thukpa and zan, households prepare pickled bamboo shoots and smoked chilli pastes as daily side dishes. These are preserved for months and eaten with rice for warmth and strength. Locally fermented greens, dried yam leaves, and river fish smoked over firewood give depth to otherwise simple meals.

The seasons deeply influence eating. In winter, hot soups and porridges dominate. During festivals like Losar and Solung, giant pots simmer with sticky rice, local pork, and fermented side condiments, shared among families and villages alike.

Meals are eaten on bamboo plates, often with wooden spoons, reinforcing the bond with nature. The food here doesn’t shout, it whispers of home, hearth, and harmony, a quiet part of India.

Assam – Clean Flavours and Calm Cooking

Assamese food flows gently like the Brahmaputra. It doesn’t rely on oil and complex spice blends. Instead, it highlights freshness. Rice is the constant. John, a small-grained aromatic rice, is especially prized. It’s served with river fish, green vegetables, and mustard oil for punch.

A signature is khar, an alkaline broth made from banana peel ash. It’s used to cook papaya and for pulses and is always served first in a meal, as a palate cleanser. Masor tenga, a light and tangy fish curry, follows with its refreshing tomato and elephant apple sourness.

On Bihu festivals, food takes centre stage. During Rongali Bihu in spring, households prepare pithas, coconut-stuffed rice cakes, steamed and pan-roasted. During Bhogali Bihu in winter, communities roast pork, dry fish, and rice cakes over bonfires, sharing seasonal bounty with joy.

Tribal communities in Assam, such as Bodos and Misings, contribute their dishes, smoked pork, fermented fish, rice beer, and green chilli chutneys. These highlight the diversity within Assamese cuisine and enrich the flavours of India with ancestral depth.

Manipur – Foraged and Fermented

Manipuri food is fierce, forested, and full of soul. Rice anchors every meal, often paired with fermented fish, boiled vegetables, and pungent chutneys. The Meitei people eat slowly, respecting each ingredient’s origin and role.

Eromba, a spicy mash of vegetables and fermented fish (ngari), is central to daily meals. Soibum, fermented bamboo shoot, is used in stews and paired with smoked meats and snails. Herbs like maroi nakupi (chive), perilla, and wild coriander add a unique fragrance.

Ooti, a gentle porridge made of rice and lentils, and chamthong, a vegetable soup, bring balance and calm. Fermentation is a sacred technique here, vegetables, soybeans, and fish are preserved for flavour and medicine.

During Lai Haraoba and Yaoshang festivals, special dishes like chak-hao kheer (black rice pudding) and steamed meat dumplings are prepared. These are offered to the gods before being shared with the community.

Manipuri cuisine is herbal, ancestral, and reverent. In every bite, it offers a sharp and memorable chapter in the Flavours of India.

Meghalaya – Pork, Smoke, and Tribal Warmth

Meghalaya food is tribal, smoky, and rugged. Rice is the heart of every plate, cooked in many forms: steamed, fermented, and fried. Pork is beloved, often cooked into celebratory dishes like jadoh, rice simmered with pork fat, blood, and spices.

Dohneiiong, pork in black sesame paste, offers a nutty depth and silky texture. In Garo homes, soda made from wood ash adds a unique alkaline touch to stews. Every tribe has its own methods. Khasi people use ginger and turmeric liberally. Jaintia kitchens love wild greens and dry fish.

Foraging is vital. Wild ferns, mushrooms, and medicinal roots are cooked gently, and pickled in mustard oil. These ingredients aren’t only food, they’re a legacy.

Rice beer, brewed at home, is poured into bamboo tumblers during weddings and harvests. Shared with song and dance, these moments are woven into the very act of eating.

Meghalaya cuisine is uncommercialised, rooted in village kitchens and sacred groves. It lends their forest-scented depth and spiritual warmth.

Mizoram – Minimal, Mild, and Smoked

Mizo food is clear, modest, and always seasonal. Rice is paired with boiled vegetables, smoked pork, chicken, and mild stews. The goal is balance, not boldness.

Vawksa rep, made of smoked pork with chillies and onion, is a staple. Bai, a stew of local greens, beans, and herbs, varies from village to village. Fermented bamboo shoots, mustard leaves, and wild ginger add sharpness.

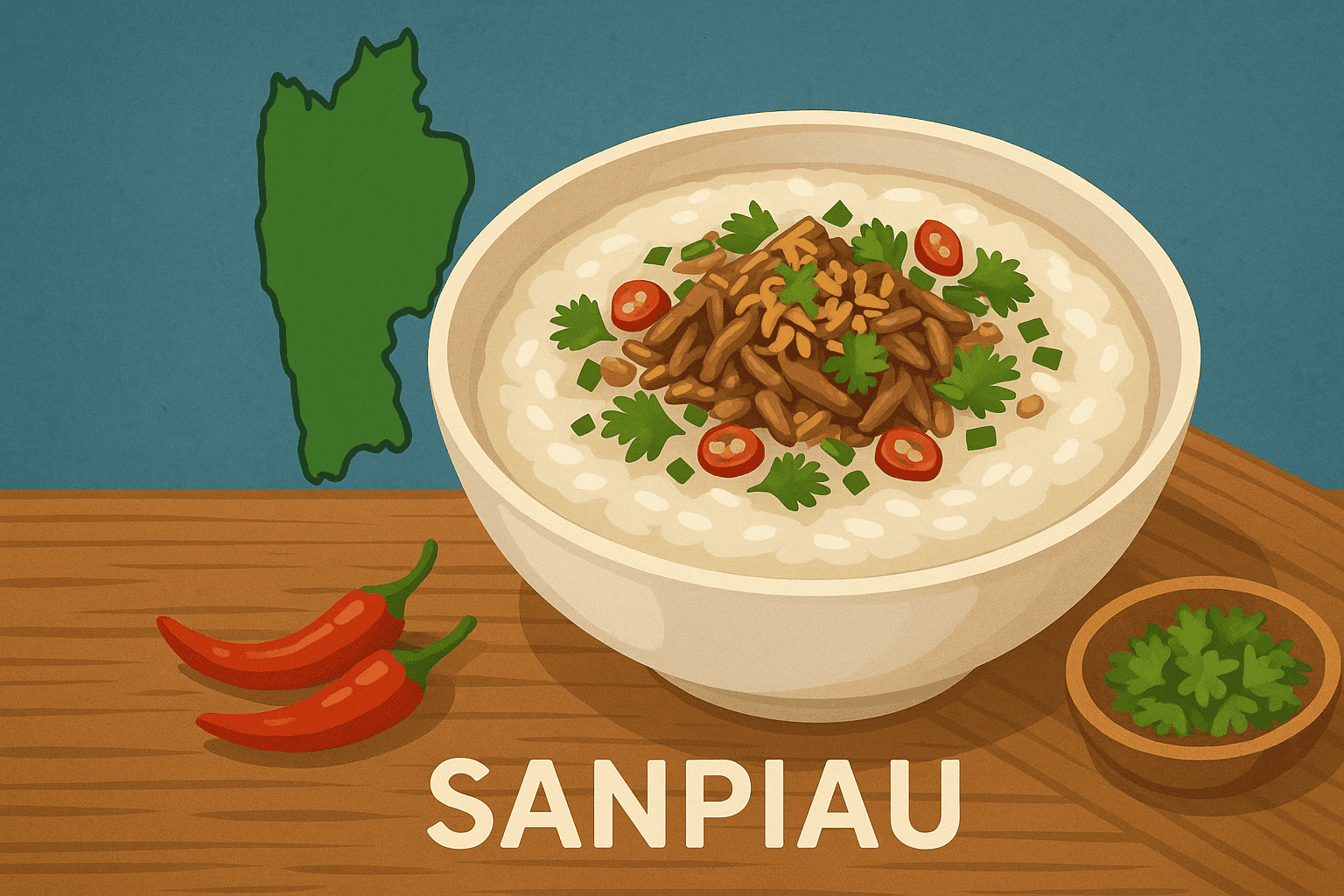

Meals follow a pattern: light breakfast, hearty lunch, porridge, and broth at dinner. Sanpiau, a rice porridge garnished with pepper and herbs, is sold at roadside stalls early in the day. It’s soul food.

Seasonal herbs like anthurium leaves and wild garlic are used for their flavour and healing power. Hunters and gatherers bring back snails, yams, and forest mushrooms to expand the palate.

Festivals like Chapchar Kut bring communities together. Shared food, rice, beer, and dance complete the celebration. Mizoram cuisine is not flashy, but it’s deeply healing. It brings a quiet clarity to the Flavours of India.

Nagaland – Fire, Ferment, and Fierce Flavour

Naga food is bold and unapologetic. Fermentation and fire define its cooking. Every tribe has its specialities, but pork, bamboo shoots, and fiery chillies are common across the state.

Smoked Pork with Bamboo Shoots is the king. The pork hung above hearth fires, absorbs smoky flavour for weeks. Fermented bamboo shoots add sourness. Akhuni, the famous fermented soybean paste, is pungent but loved for its depth.

Galho, a porridge of rice, herbs, and smoked meat, is often eaten daily. Sticky rice cakes and boiled wild vegetables round out the meal. Dishes are rarely fried, boiling and smoking rule here.

Bhut Jolokia, one of the world’s hottest chillies, is used sparingly but effectively. Naga chutneys (locally called ‘ghutney’) are fierce, often combining tomato, fermented fish, and chillies into a volcanic blend.

During the Hornbill Festival, tribes cook together. Giant feasts feature buffalo meat, millet pancakes, and wild foraged greens. It’s more than food, it’s identity.

Nagaland cuisine adds a fearless spirit, proving food can be a form of strength.

Tripura – Forest Wisdom and Fermented Strength

Tripuri food is humble, wild, and full of forest wisdom. The centre of this cuisine is Mui Borok, the traditional food of the Tripuri tribes. It focuses on balance, freshness, and light preparation.

Rice is always present, served with vegetables, river fish, and pork. Berma, a dried and fermented fish, is the signature flavour. It adds sourness and umami to dishes without overpowering them.

Wahan Mosdeng, a spicy pork salad with roasted bamboo shoots, is popular in tribal homes. Green chutneys made with fermented shrimp and wild garlic accompany every meal.

Tripura’s forests offer mushrooms, yams, snails, and edible flowers. People forage these seasonally. Hunting once played a role in the food system, especially among tribal groups, though it’s now limited to specific regions.

Festivals like Garia Puja bring shared meals and rice beer into focus. Each tribe has its take on Mui Borok, some lean spicy, others mild and smokier. This diversity reflects the layered contribution of Tripura cuisine to the Flavours of India.

A Journey Worth Taking

Exploring North East Indian food is a journey into India’s culinary soul. Here, the Flavours of India come alive through fire, fermentation, and forest bounty. They are bold, rooted, and refreshingly real.

Itinerary Ideas for Gourmet Explorers

For explorers who think the optimal way to experience a location is through its cuisine, India provides a sensory odyssey unequalled anywhere else. A carefully planned diy food trail can open up tastes and experiences that no standard itinerary ever will.

Begin your voyage at Ahmedabad, where each bylane narrates a story in farsan. Wake up to fresh khaman and jalebi-fafda from heritage sweet shops at Manek Chowk, and dive into the elaborate Gujarati thali at traditional bhasanis like Agashiye. Winter is the prime time to enjoy undhiyu and adadiya pak, local favourites that are sold for a limited number of months.

Next, it’s off to Kolkata, the city where culture and cuisine stride side by side. Hit the iconic Indian Coffee House on College Street for kabiraji cutlet and adda, then meander into nearby sweet shops for rasgulla and sandesh. The spring season, around Poila Boishakh (Bengali New Year), is the best time to enjoy celebratory feasts and fresh hilsa.

Head still further south to Kerala, where food is inextricable from the land and its verdant, water-imbued terrain. Feast on a banana-leaf sadhya during Onam in August–September, and taste appam-stew breakfasts in Kochi, seafood curries on the Malabar coast all year round.

You can just complete your gastronomic journey in the North East, where cuisine is still gloriously uncommercialised and deeply traditional. Go to the tribal markets in Kohima, Aizawl, and sample the fermented bamboo shoot delicacies, smoked meats and rice beer. The winter and early spring months carry us into our traditional harvest festivals, which makes it the perfect season to experience community feasts and savour seasonal forest-foraged ingredients.

This trail isn’t about checking plates off a list; it’s about submersion. It’s where you exchange brochures for tiffins and souvenirs for recipes and snapshots for soul-soothing memories, one plate at a time.

Read More: Latest