Beyond steel or leaf, the Indian tiffin remains an everyday love letter wrapped in tradition.

Few objects in India command as much silent reverence as the tiffin box. Usually cylindrical, often made of stainless steel, and composed of two to four stacked containers held together by a sturdy clasp, the tiffin box (or lunch boxes bags) is at once utilitarian and symbolic. It begins its journey in the intimacy of the kitchen, travels through chaotic streets, and finally opens with a click that signals not only nourishment but warmth, care, and even love. For generations of Indians, the tiffin has been less a container and more a ritual, a presence that bridges the distance between home and the outside world.

The word “tiffin” itself is a curious relic of colonial India. In the early nineteenth century, British officers stationed in the subcontinent struggled with the punishing heat that made heavy afternoon luncheons undesirable. To adapt, they began eating lighter meals and borrowed the slang “tiff” — meaning a small drink or repast — and reshaped it into “tiffin.” Initially, it simply denoted a snack.

But as the word passed from British mouths into Indian kitchens, it took on a character that was distinctly Indian. Instead of referring to a small meal, “tiffin” came to denote the vessel in which food was carried and, by extension, the routine of taking home food on the move. The colonial word was domesticated, repurposed, and made Indian in spirit.

This metamorphosis proved significant in a rapidly urbanizing society. By the late nineteenth century, India’s cities were growing fast, railways connected industrial centers, and more Indians were working away from home. The challenge was that eating away from home also meant eating outsid, which was never truly trusted.

In India, food is not just about nutrition but is entwined with memory, ritual purity, and the emotional labor of the household. The tiffin emerged as the solution: it allowed families to carry the sanctity of homemade meals into schools, factories, offices, and long train journeys.

It is this power to collapse distance that makes the tiffin a ritual more than an object. Schoolchildren still remember fondly the question asked with great excitement across lunch breaks: “What have you brought in your tiffin today?” The tiffin hour was often when friendships were sealed, trades made, and dishes sampled from unfamiliar kitchens. In workplaces too, the pooling together of tiffins often transformed colleagues into confidants.

The act of eating together out of one another’s boxes blurred class and regional divides, creating miniature communal buffets that embodied India’s belief: that food binds people more deeply than conversation does.

The Indian tiffin, then, is a remarkable invention of necessity and love. It combines thrift with affection, practicality with symbolism. It has outlasted its colonial origins to become a cultural artifact in its own right, as integral to the Indian workday as tea breaks or evening prayers.

Mumbai’s Dabbawalas – The City’s Midday Miracle

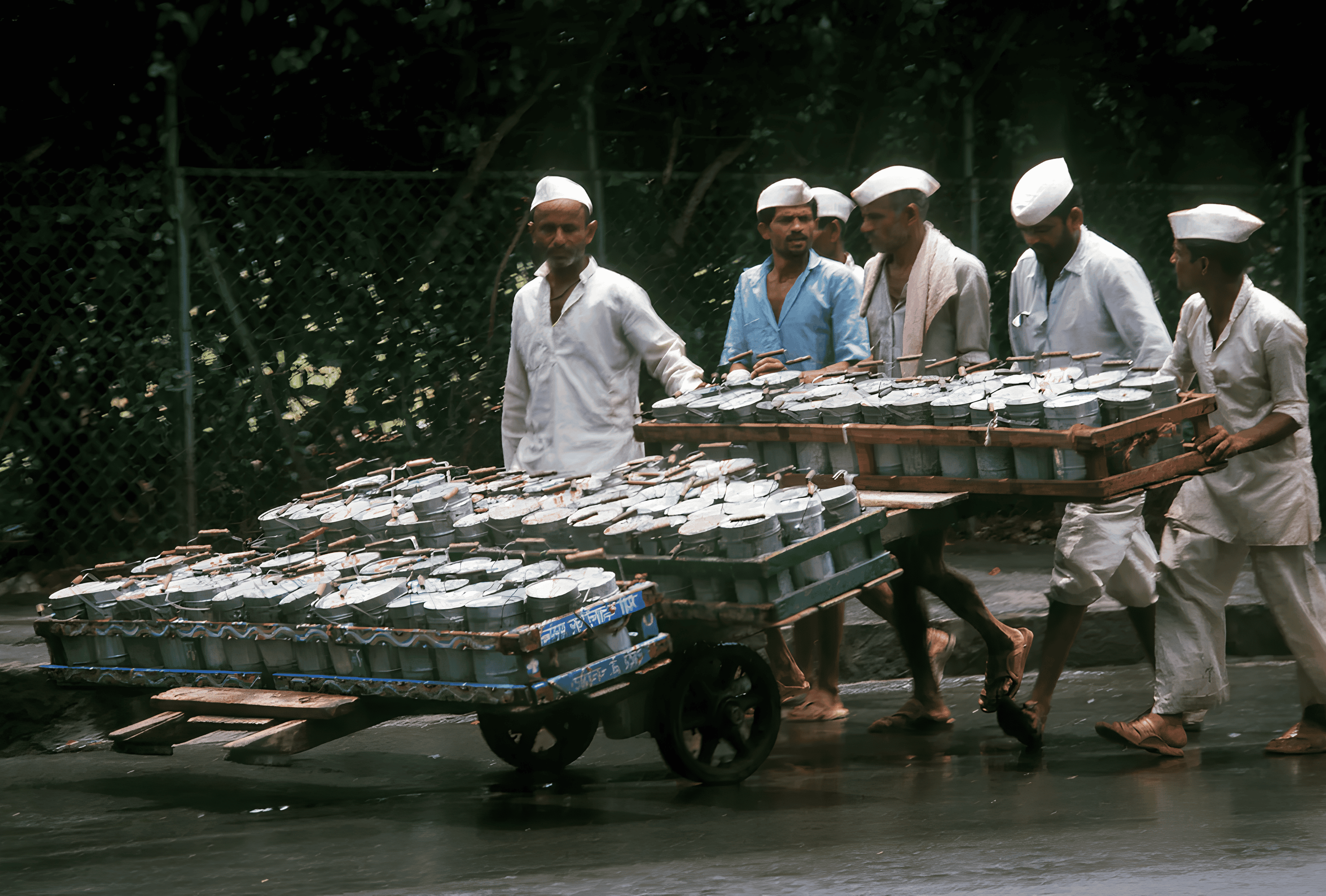

If the tiffin is India’s most faithful companion, the dabbawalas of Mumbai are its most extraordinary custodians. In one of the world’s most frenetic cities, where millions live hours away from their workplaces and commute daily on overcrowded trains, the act of enjoy homecooked meals every day precisely on time seems miraculous. Yet, every day without fail, an army of white-clad men deliver around two hundred thousand steel tiffin to go containers to office desks with near-perfect accuracy.

The method is deceptively simple. In the late morning, dabbawalas, most of whom hail from rural Maharashtra, fan out across residential areas to collect tiffins from homes. Each box is indelibly marked with codes and symbols that indicate railway stations, destination zones, and delivery addresses. At sorting points near local train stations, the boxes are organized and then loaded onto trains, traveling across the city crisscrossed by suburban rail. At the other end, they are picked up again, sorted afresh, and ferried on bicycles or headloads to their final destinations: the corporate offices in Nariman Point, the banks in Fort, or the IT hubs near Andheri.

This happens with astonishing efficiency. For decades, scholars, management gurus, and global leaders have marveled at the dabbawala system’s Six Sigma accuracy, meaning error rates lower than one in several million deliveries.

Harvard Business School studied their operations. The BBC and National Geographic documented them. Prince Charles insisted on meeting them. Richard Branson cycled with them for a day. But for Mumbaikars, it is not about statistics or fame. For them, dabbawalas embody reliability, resilience, and the comfort that, even in a city of anonymous rush, someone ensures a thread of home still reaches your desk at noon.

Yet the service is not merely logistical; it is deeply emotional. There are countless stories of families conveying affection and messages through the tiffin. A husband making up for a quarrel by sending a favorite sweet dish, a wife writing a note and slipping it beneath a pile of rotis, or parents sneaking in a surprise sweet snack on exam days for anxious children — these little gestures carried across the city by dabbawalas illustrate how a lunchbox could become a love-letter in disguise. For workers who live in cramped hostels and far away from their families, the arrival of the tiffin often means more than sustenance; it is reassurance, a daily whisper from loved ones.

The dabbawalas themselves live lives of immense pride and discipline. Organised as a cooperative trust, they share profits equally and treat their work as duty to society. Even in times of crisis, such as the devastating floods of 2005, when Mumbai was submerged, dabbawalas waded through waist-deep waters to complete deliveries.

During the lockdown in 2020, when offices shut, many dabbawalas faced financial ruin, reminding the city of how indispensable they had been for over a century. Citizens rallied to provide relief, affirming once again their status not as service providers, but as cultural icons.

In many ways, the Mumbai dabbawala is a metaphor for the city itself: relentless, ingenious, imperfectly perfect. His cycle weaving between buses, his simple white cap visible through crowded lanes, symbolizes trust. And with every tiffin he delivers, he keeps alive not only a stomach but also an emotional connection stretched across Mumbai’s exhausting distances.

Kerala’s Banana Leaf Magic – Pothichoru

Travel far south of Mumbai, into the verdant lanes of Kerala, and the tiffin takes a completely different form. Here, the polished gleam of steel is replaced by the lush green of banana leaves. The pothichoru, or parcelled meal, remains Kerala’s most nostalgic and sustainable version of the lunchbox.

The ritual of preparing pothichoru is itself an aesthetic delight. A fresh banana leaf is first washed and cut to size. Onto its glossy surface is ladled warm rice, over which come a variety of accompaniments: spicy rasam, mild moru curry made with curd, coconut-based thoran, tangy chammandi, and, very often, a sliver of fried fish or an omelette. Once packed, the leaf is folded into a neat rectangle and tied with natural thread, forming a compact, self-contained bundle.

This green parcel is not just food. It is memory and emotion wrapped together. For Keralites, the scent of warm rice steaming inside a banana leaf evokes childhood mornings when mothers or grandmothers rose at dawn to prepare meals for children heading to school or men trudging off to work. The experience of unwrapping a pothichoru on a long train journey remains vivid in the collective memory of Kerala: compartments filling with earthy aromas, passengers exchanging pickles or fried papads with strangers, and a meal that created instant companionship.

Beyond nostalgia, pothichoru also embodies sustainability. Banana leaves are plentiful in Kerala, renewable, and biodegradable. They leave behind no waste, unlike plastic or foil, and add a subtle fragrance that makes the meal taste fresher. Today, when sustainability dominates global discourse, pothichoru stands as ancient proof that eco-friendly solutions were always available in traditional practices.

Even in corporate offices of modern Kochi, Thiruvananthapuram, or Kozhikode, where employees carry laptops and smartphones, the sight of a pothichoru in one corner can transport a worker back to ancestral kitchens and hearths. It symbolizes continuity and rootedness, a reminder that no matter how fast one moves in the global world, identity and belonging are often folded quietly inside a banana leaf.

Southern Tiffin Rooms – Food as Everyday Celebration

In southern India, the word “tiffin” diverges yet again, demonstrating the richness of regional interpretations. Here, tiffin does not always mean a lunchbox carried to work. Instead, it often refers to light meals served in eateries between breakfast and dinner.

The southern “tiffin room” is an institution in its own right. Walk into one in Chennai’s Mylapore or Bengaluru’s Basavangudi, and you are immediately engulfed in the sounds and smells of communal eating. Waiters in starched uniforms rush past tables balancing trays laden with towering masala dosas, soft idlis glistening with ghee, crisp medu vadas swimming in sambhar, and tumblers of filter coffee served hot and frothy. The air vibrates with chatter in Tamil or Kannada, punctuated by the clatter of steel plates and the hiss of dosas being cooked on massive flat griddles.

Unlike global brunches that are indulgent luxuries, tiffin in southern India is routine. It is nourishment for every class, every age group, every profession. College students drop in between lectures, elderly couples arrive for evening coffee and pongal, families sit in long lines for Sunday breakfasts, and office workers on tight schedules eat quickly before rushing back.

The southern tiffin kadai thus embodies democracy in food. Rich and poor, elite and working-class, all share the same menu. Food here is not ornamented but wholesome, not curated for Instagram but anchored in tradition. Eating in these spaces is not just about filling the stomach; it is about participating in a social fabric where food is both communal and egalitarian.

This dual existence of the tiffin — as a box at home in the north and west, and as a meal in restaurants in the south — reveals the adaptability of Indian culinary culture. It shows how a single word can contain multitudes of meaning, just as the nation it belongs to does.

Regional Flavours – India’s Culinary Atlas of Tiffins

To travel across India with an eye on tiffins is to chart a culinary atlas as diverse as the subcontinent itself. Every state contributes its own portable interpretation of lunch, revealing geography, history, and cultural memory in every bite.

In Bengal, the tiffin finds its essence in the eternal pairing of rice and fish curry. A mound of soft white rice and a light mustard-seed-infused fish curry create a meal that is simple yet profoundly satisfying. Sometimes an extra box with mishti doi, the famous sweetened yogurt, accompanies it. Here, as always, Bengal’s tiffin reflects its riverine landscape and eternal intimacy with fish.

In Gujarat, the tiffin box most often holds thepla, a spiced flatbread that remains soft for days. Accompanied by tangy mango pickle or curd, thepla is not only nourishing but long-lasting, making it the perfect food for long train journeys or even for air travel. Many Gujaratis traveling abroad proudly carry stacks of thepla in their luggage, earning it the nickname “the traveler’s roti.” Its endurance and ease symbolize Gujarati pragmatism and resilience.

Punjab, by contrast, celebrates abundance. A Punjabi tiffin is heavy with stuffed parathas dripping with butter, wrapped in foil, and paired with pickle and dahi. Sometimes rajma-chawal or chole accompany the meal. Punjabi schoolchildren still recall proudly opening their dabbas to show off thick parathas, which would often lure classmates from other regions. The Punjabi lunchbox, much like Punjabi culture, is generous, hospitable, and hearty.

Maharashtrian tiffins are often filled with poha, usal-pav, or zunka bhakri. These are modest dishes, often rustic, yet deeply nourishing. Many households also include a small morsel of sweet, a symbolic wish that the day may proceed with sweetness.

In Rajasthan, where the desert climate dictates preservation, the lunchbox often carries bajra rotis paired with fiery garlic chutney and ker-sangri, a hardy bean-and-berry dish that withstands harsh conditions. These tiffins mirror the land’s toughness but also its ingenuity in creating variety out of scarcity.

Odisha contributes the most unusual entry: pakhala, a dish of slightly fermented rice mixed with water and yogurt, accompanied by fried vegetables. Carried in clay pots or steel boxes, it is a cooling meal in summer, refreshingly simple and utterly unique.

Andhra Pradesh and Telangana favor tangy, spicy tamarind rice, lemon rice, or gongura rice, their bold flavors lingering for hours. Himachal and Uttarakhand carry rotis made from millets like mandua, coupled with rustic sabzis and the famous pahadi rajma. The North-East, too often left out of mainstream culinary discussions, has its own portable delights: sticky rice parcels wrapped in leaves, smoked pork distributed in small packets, or bamboo-shoot pickles that travel well.

Each of these reveals something more than just culinary preference. They are microhistories of survival, adaptation, and celebration. They show how the Indian tiffin is not a monolith but a kaleidoscope — carrying rivers, deserts, mountains, and coasts within its compartments.

The Sociology of Sharing: More than a Meal

What perhaps makes India’s tiffin most unique is not merely what it contains, but how it is consumed. In no other culture is the act of sharing lunchboxes so deeply ingrained.

In schools, the opening of tiffins is eagerly awaited. Children crowd around one another, opening lids with curiosity and delight. “What did you bring today?” is not just a question but an invitation to exchange. A paratha might be swapped for fried rice, a gulab jamun traded for paneer curry, and friends learn both generosity and curiosity through this routine. In many cases, children’s first encounters with other regional cuisines occur not at restaurants but across the modest steel compartments of their classmates’ dabbas.

Offices carry the same culture forward. At noon in Indian workplaces, groups assemble around makeshift tables, pooling their individual dabbas into communal feasts. In these moments, the strict hierarchies of corporate titles soften. A manager might reach across for a spoonful of sambhar from a junior’s box; an intern might try Gujarati kadhi for the first time. More than eating, these moments generate bonds of trust, camaraderie, and shared identity.

In factories too, the lunch break often resembles a community picnic. Workers sit in circles, their tiffins forming common pools. Unlike in the West, where a boxed lunch is typically consumed solo, in India the tiffin creates community. It reflects the cultural philosophy that food acquires meaning only when shared.

Tiffin as Heritage and Modern Innovation

The tiffin is as much a cultural artifact as the sari or the sitar. It speaks of thrift, balance, and affection — elements that define the Indian household. Each compartment embodies the Indian food philosophy of combining cereals, vegetables, proteins, and sweets in harmony. The durability of the steel box itself mirrors the resilience of Indian familial practices, surviving urban chaos and modern alienation.

At the same time, the tiffin has adapted gracefully to modernity. Startups across India now thrive on “tiffin services,” offering homecooked subscription meals for urban professionals who live away from families. Social media has rejuvenated its appeal, with Instagram feeds dedicated to “lunchbox art” featuring bright quinoa pulaos, avocado parathas, or millet-based dosas neatly packed into bento-style tiffins. Eco-conscious citizens return to banana leaves and cloth carriers as alternatives to plastic.

In the Indian diaspora too, the tiffin remains an anchor. Few things capture the emotional tug of migration better than opening a stainless-steel box of dal and rotis in a foreign office in London or New Jersey. In a cafeteria where burgers dominate, the Indian professional’s dabba becomes a statement of belonging and nostalgia. It signals both pride and longing, an edible reminder of home.

Why the Tiffin Endures

The endurance of the tiffin lies in its unique combination of utility, emotion, and philosophy. On a practical level, it is cost-effective, healthier than fast food, and remarkably resilient. On a cultural level, it collapses distance, making the absent present through the flavor of a familiar sabzi cooked hours earlier in a home kitchen. On an environmental level, it is sustainable, requiring no plastic, no disposables, and almost no waste.

But beyond practicality, its endurance lies in meaning. A tiffin is an everyday love letter. It says: I thought of you in the morning, I cooked for you, I packed for you, and now I am with you even when I am not. It represents continuity in a changing world, roots in an age of uprooting. This is why, despite delivery apps, global chains, and convenience foods, the Indian tiffin remains unmatched.

Home Inside a Box

To understand India, one must not only taste its famous curries or snacks at restaurants. One must observe the quiet miracle of the tiffin box. See the dabbawalas cycling through Mumbai rains with towers of boxes. Watch a schoolchild barter chocolate for chutney during recess. Witness colleagues gathering to swap bites of paratha and sambhar. Or smell the fragrance of a banana leaf parcel unwrapped on a Kerala train.

In these modest rituals lies the essence of India’s culinary soul: food that nourishes not just bodies but bonds. The tiffin endures because it is not just a meal, but a story. It tells of families that rise early, of cities that depend on invisible heroes, of regions that share their flavors, of strangers becoming friends over stainless steel.

Every time a tiffin lid clicks open, India reveals itself — affectionate, inventive, diverse, and enduring. It is not exaggeration but truth to say: the Indian tiffin box is everyday magic.

Read more – Latest