Patu Keswani: How an accidental hotelier built a brand defined by precision and purpose, with design as discipline, data as direction, and dignity at its core.

Some founders build companies. Then some founders build cultures. Patu Keswani belongs firmly to the second kind. His story does not begin in hospitality, and it never pretends it was destiny. It begins with the inheritance of something rarer than capital: an awareness of what life looks like when opportunity is present, and when it is not.

“I don’t think I was meant for hospitality,” he says candidly. “A lot of things in my life happened by chance.” Keswani’s journey unfolds as a sequence of pivots that only make sense in reverse. Engineering, architecture, consulting, a corporate ladder inside the Tatas, an early plan to retire, and then a mid-market hotel brand that would go on to scale across India. Each stage appears accidental. Together, they look almost engineered.

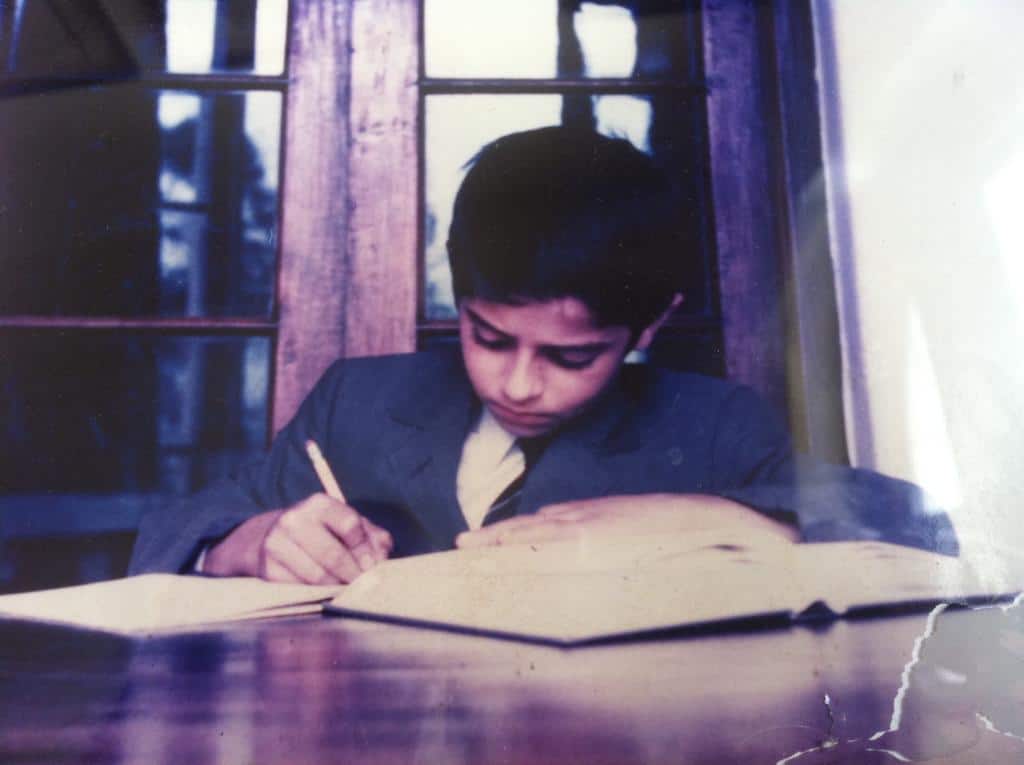

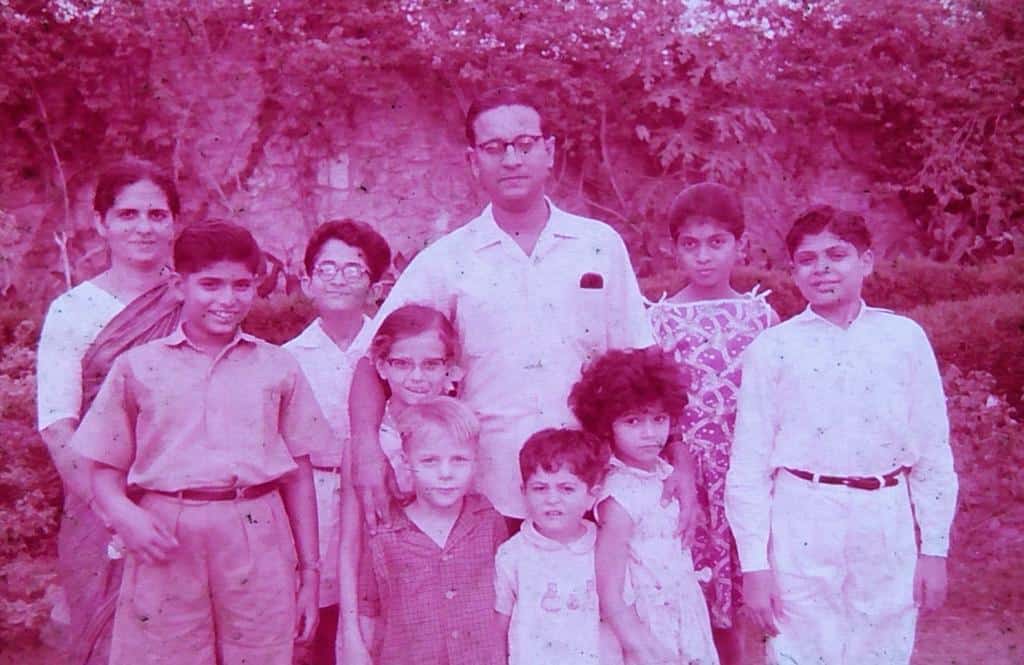

A childhood shaped by two opposite maps of India

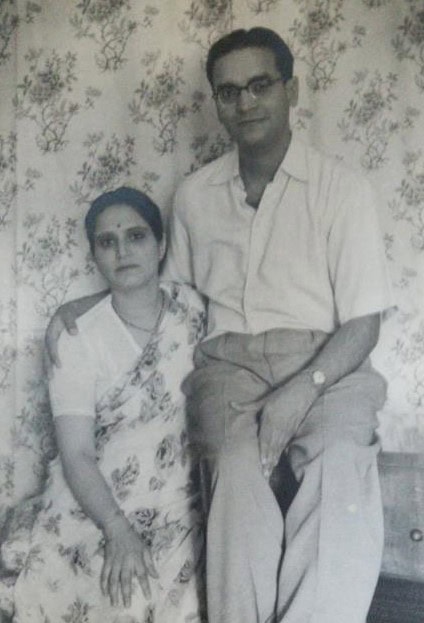

Patu Keswani was born in February 1959, the youngest of three children. His father’s early life was marked by extreme poverty in what was then undivided India, a childhood defined by loss, responsibility, and scholarships that kept education alive. The story is not shared for sentiment. It is shared as an explanation for the moral grammar Keswani grew up with: an instinctive discomfort with inequality, and a deep respect for people who work hard in silence.

His mother’s background carried a different kind of strength. A doctor who served in the Indian Army, raised with confidence and independence, she represented possibility at a time when most women were not granted it. Keswani recalls how she took early retirement to care for him, a decision that stayed with him as a mixture of gratitude and guilt.

Years later, a chance encounter with one of her batchmates, now a senior officer, brought the sacrifice into focus. “She told me, half joking, half wistfully, ‘If it wasn’t for you, I might have become a general too,’” he recalls. “That stayed with me.”

Between these two influences, Keswani grew up acutely aware of inequality. The result was a worldview that never let him forget how unevenly life distributes starting points. “You and I are fortunate,” he says. “We were born in families where opportunity existed. That alone changes everything.” It is a thought that returns often in his reflections, anchoring both his personal choices and the culture he would later build.

Accidental Foundations: How Detours Shaped a Philosophy of Work

Patu Keswani often laughs when people assume he trained for a career in hospitality. “I had absolutely no intention of being in hotels,” he says candidly. “It wasn’t even on my list,” he adds. His academic path, as he explains, ran in an entirely different direction: Computer Science and Electrical Engineering at IIT Delhi, followed by an MBA at IIM Calcutta. Somewhere along the way, almost incidentally, he took architecture as a minor. At the time, it barely registered as consequential. “I didn’t think it would matter,” he says. “It just seemed intellectually interesting,” he adds.

It was only years later that the significance of that exposure became clear. “Architecture teaches you how to think about space,” he says. “But more importantly, it teaches you how to think about utilisation.” That lesson, he notes, sits at the core of hospitality. “In hotels, utilisation is everything,” he adds. “You can build something that looks premium, but if it doesn’t work operationally, people suffer.” The insight reflects the way his thinking consistently bridges design intent with operational reality, an approach that would quietly shape the Lemon Tree philosophy.

Keswani is equally open about how little of his early life unfolded according to plan. Even moments that appeared decisive at the time arrived through circumstance rather than strategy. He recalls securing admission to a foreign university, a move that felt like the obvious next step, only for illness to intervene. He could not travel. “At that moment, it felt like a setback,” he says. “I was quite disappointed,” he admits. With time, however, the meaning of that interruption shifted. “Later, I realised it anchored me in India.”

That experience became an early marker of a pattern he would recognise repeatedly in his journey. “What looks like a detour often turns out to be the main road.” Perspective, he reflects, only arrives later. “You only see that in hindsight,” he says.

Leadership lesson that began in the basement

Patu Keswani entered corporate life through the Tata Administrative Service, drawn by what he describes as “purpose and nation-building.” His path eventually took him into the hotel business, despite having no background in it.

When he was posted to a senior role at a flagship hotel, he was advised to do something counterintuitive. “I was told, ‘For three months, behave like an intern. Ask questions. Don’t pretend you know anything,” he says.

It is here that his story starts to resemble a leadership case study. He took the advice literally. He worked in housekeeping, stewarding, room service, and laundry. He stood for nine hours a day. “At the end of the day, you are exhausted,” he says. “The blood rushes to your feet. The work is repetitive. Guests don’t even see you.”

One moment stayed with him. “A batchmate from business school stayed at the hotel,” he says. “I decided to be his bellboy. I carried his bag, rode the elevator with him.

He didn’t recognise me at all. Not once.” He pauses. “That’s when you understand how invisible this work can feel.”

The lesson is foundational. “Hotels cost hundreds of crores to build,” he says. “But returns come from people doing some of the toughest, most thankless jobs.

And then we expect them to smile and deliver service from the heart.” He adds quietly, “That only works if dignity exists inside the organisation first.”

It was during these years that Patu Keswani formed a strong view of leadership. He speaks candidly about what he saw in certain styles of power: patronage over merit, loyalty demanded rather than earned, promotion based on closeness rather than competence. He says he learned two things at once. What to do, and what not to do.

Both would later become the invisible blueprint behind Lemon Tree.

Lemon Tree: the mid-market gap, built with ratios and heart

By his late thirties, Keswani wanted financial freedom. He had moved into consulting, earned well, and even toyed with the idea of early retirement. “For a while, I thought I was done,” he says. “I thought I had cracked the formula,” he adds. Then practicality intervened. Children, education, inflation, time. “You realise you need something that grows,” he says. “Money that stands still actually moves backwards,” he adds. What he was looking for, he realised, was an inflation hedge.

The decision to build a hotel came almost matter-of-factly. India, Keswani observed, had an abundance of luxury hotels but very little in the organised mid-market space with consistent standards. He explains the opportunity through a simple analogy. “If business class seats are always full,” he says, “there is clearly demand sitting below.” “The same logic applies everywhere,” he adds. If five-star hotels were thriving, demand for three- and four-star experiences was clearly being left underserved.

The timing was perfect, even if it didn’t appear so at the time. Keswani built a 49-room hotel in Udyog Vihar using principles he had developed earlier while analysing why different hotels performed differently. He had once broken the hotel business into hundreds of datapoints: corridor illumination, air-conditioning load per square foot, electricity consumption, housekeeping productivity, staffing ratios. “I literally looked at everything,” he says. “How much light does a corridor need. How many rooms can one housekeeper realistically service?” he adds. He compared top performers across multiple properties, captured the best practices, and turned them into a design-and-operations logic.

This first hotel was built exactly on those ratios. It worked.

His model was sharply Indian in its understanding of guest behaviour. “Land and construction are expensive. Labour is comparatively affordable. Indian guests expect service, even at lower price points, ” he shares. So he offered full service at roughly half the cost of a five-star, with a smaller, more basic room, and one uncompromising rule: never dilute location quality.

The brand that followed, Lemon Tree, became a direct translation of Keswani’s worldview into hospitality—smart design guided by ratios, operational discipline rooted in data, and a deep respect for the people delivering the experience.

From Momentum to Market: How Growth Made the IPO Inevitable

Keswani is candid that an IPO was never part of his original plan. “I never thought we would go public. When we started, it was just an idea and a dream,” he says. In those early years, ambition was anchored firmly in execution. “The first hotel was built on time, in budget, in quality. The second hotel was built the same way, and it made a lot of money.” What followed was a pace of expansion that even surprised him. “Then came the third hotel in Pune, the fourth in Goa, and by 2006, we had five hotels and twenty-three under construction.”

Looking back, Keswani admits the scale arrived faster than expected. “I myself couldn’t believe how quickly people were growing,” he recalls. “It was very difficult in those days to build hotels and to have money to build them. But we were making so much money that we could do it.”

That performance soon drew the attention of global capital. “Then Warburg Pincus, one of the largest private equity firms in the world, came and said, ‘Your company is worth eight hundred crores.’ I was shocked.” Their terms were direct. “They said, ‘We want twenty-five per cent,’ so they put in another two hundred and seventy crores.” Keswani’s response was instinctive. “They gave me the money, and I put it straight into more hotels.” Kotak followed soon after, investing a few hundred crores more.

By this stage, Lemon Tree’s positioning was sharply defined. “We had three brands — Lemon Tree, Lemon Tree Premier, which was four-star, and Red Fox, which was two-star. We were targeting everyone except luxury and guest houses.” The real shift in perspective, however, came in 2012 with an unexpected outreach. “I got this random mail from APG — a Dutch pension fund I had never heard of. I said, “Who are these people?” He laughs at the memory. “Pure serendipity.”

With long-term global institutional capital on board, responsibility took on a different meaning. “Once serious capital comes in, you have to think responsibly. Funds have a life cycle. Pension funds have to exit. Liquidity cannot be emotional.” The logic, he says, became unavoidable. “These are long-term investors, but even long-term capital needs a clear way out. The only sensible way to do that is through a listing.”

Yet Keswani was determined that ownership would not remain concentrated at the top. “I told my people, take shares. When the hotels make money, on dividends, you make some income for the rest of your life.” He acted decisively. “I actually gave shares to about eight hundred people. About eight per cent of the company. Today, that’s worth about eleven hundred crores.” The outcome remains deeply personal. “A lot of them made enough money to buy houses. Some people had twenty crores in the bank. Even today, there are such people.”

Structurally, the IPO thinking was equally deliberate. “Globally, look at Marriott or Hilton. They don’t own hotels. They manage, they brand, they distribute.” What began as a requirement evolved into a strategy. “What started as a necessity became a core competence.”

The listing, he clarifies, will be for the asset-owning company. “We list, we dilute over time, we keep raising capital, and we keep building.” For Keswani, the purpose of going public is unambiguous. “An IPO is not a destination. It’s a tool—to give liquidity, to reward belief, and to make sure the company outlives the founder.”

Building People Into the System: Inclusion by Design, Not Charity

If Lemon Tree’s growth story is about capital and scale, its most distinctive legacy is about people.

Keswani describes an early decision that became a turning point: hiring two deaf employees for stewarding roles. He expected it to be a small gesture of gratitude to life and its many rewarding moments. What followed surprised him. One employee’s mother came to meet him. She explained how employment had transformed her son’s life. “That moment changed how I thought,” Keswani says. “It stopped being theoretical,” he adds.

He made a choice that would define Lemon Tree’s identity: inclusion, yes, but never as charity. “Charity is not sustainable,” he says. “It makes people dependent. Systems, however, are sustainable.” Roles had to be designed so that the disability was irrelevant. Teams would be trained to communicate. Systems would be built to make capability visible. “You don’t do favours,” he says. “You redesign work,” he adds.

From there, Lemon Tree expanded hiring across categories: speech and hearing impaired employees, acid attack survivors in useful roles, people with Down syndrome in repetitive set-up roles where they often excelled, and later, individuals who were educationally deprived but could be trained into functional competence. The organisation became, in his words, a skilling institute as much as a hotel company. People joined on minimum wages, learned, and then moved into better-paying jobs across the industry.

Lemon Tree became a pipeline for talent that the rest of the market had been ignoring.

In a sector obsessed with guest-facing polish, this was an unusually structural approach to social responsibility. Not a CSR campaign. A workforce design philosophy.

The next chapter: stepping back, thinking forward

Today, Keswani speaks like someone who has outgrown the thrill of scale. “I get bored with largeness,” he says. “Size is not a challenge anymore,” he admits.

He is more interested in building the next layer. Fresh leadership has been brought in to run the core businesses while he moves toward technology, systems, and future strategy.

He talks about separating the hard asset business and the soft brand business, recognising that globally, hotel brands often thrive as asset-light operators while ownership sits with institutions. He speaks of building technology capabilities for distribution, revenue management, and AI-driven sales intelligence, initially for internal use and eventually as a service for the wider hotel market. “The next frontiers are all digital,” he says.

He also points to a larger shift he sees coming in India: the dominance of unbranded hotels, particularly in the mid and lower segments. For him, the next opportunity lies in consolidation, better distribution, and brand-led trust in a fragmented market.

And yet, for all the business architecture, his emotional compass returns to the same place it began: what will he do with personal wealth, beyond the company?

“I have made wealth,” he says. “That, for me, means responsibility.” He names three priorities with clarity: girl-child education, women’s employment, and opportunity-deprived Indians. “These are the gaps that matter,” he says.

The language is not performative. It is almost clinical. This is where inequity begins, and this is where he wants to intervene. He pauses, then adds, almost as a footnote, “I don’t think I am special. A lot worked in my favour. The least I can do is make sure it works for others, too.”

The founder who never tried to sound like one

Keswani’s story is compelling because it refuses glamour. He does not present himself as a genius. He insists on luck, timing, and accidental competencies. But beneath that humility is something more deliberate: a mind that turns experience into systems, and systems into outcomes.

He learned hospitality by doing the hardest work first. He built a hotel company by reading the market accurately and respecting how Indians travel. He scaled by trusting people and rewarding risk. And he created a culture where inclusion was not a headline, but an operating principle.

That is what makes Patu Keswani’s milestones matter. Not the size of the company alone, but the kind of company it became.

Read More: Latest