How mistaken ideas, bold measurements, and distant galaxies reshaped our understanding of the universe

For most of human history, the night sky felt intimate and contained. Stars appeared fixed, orderly, and close enough to belong to a single grand design. Early astronomers believed they were mapping the entire cosmos simply by charting what the eye and telescope could see. The universe, in this worldview, had edges. It had a centre. And humanity believed it knew roughly where it stood.

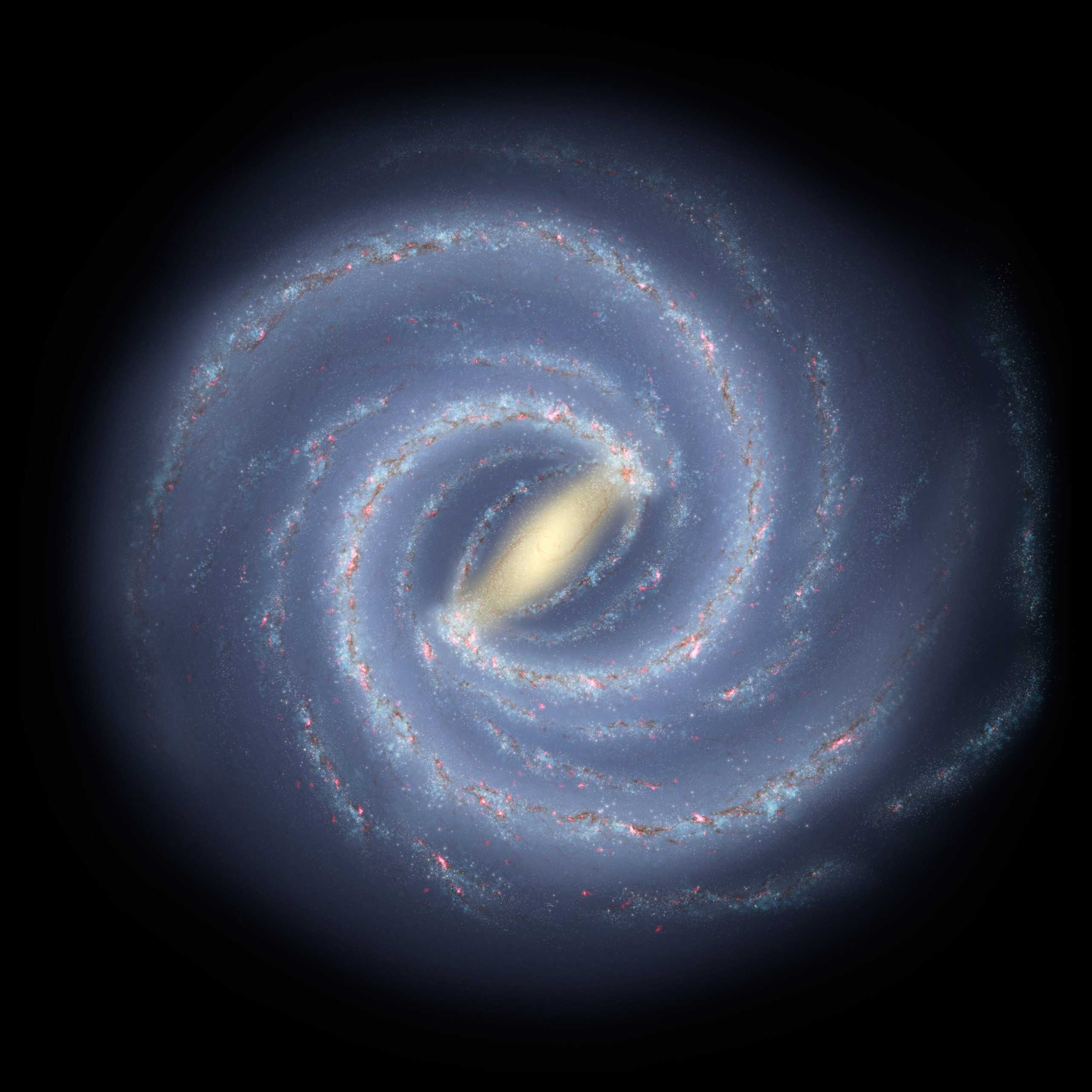

The Milky Way, our home galaxy, held a special place in this understanding. Its pale, milky band stretched across the sky like a luminous river, and astronomers assumed it was not just a feature of the universe, but the universe itself. All stars were thought to reside within this vast but finite stellar system. Beyond it, there was little reason to imagine anything else.

Yet even within this comforting certainty, small contradictions began to appear. Scattered among the stars were faint, fuzzy patches of light. They were neither sharp points like stars nor clearly defined like planets. Some appeared cloudy. Others showed delicate spiral shapes under stronger telescopes. They did not twinkle. They did not move like nearby objects. And no matter how closely astronomers looked, these objects refused to resolve neatly into individual stars.

These hazy forms were labelled nebulae, a catch-all term born out of uncertainty rather than understanding. Most were assumed to be clouds of gas or unresolved star clusters, safely contained within the Milky Way. It was easier to believe this than to confront a more unsettling possibility.

If these objects were not part of our galaxy, then the universe was far larger than anyone had dared to imagine. For a time, that thought remained too radical to accept.

The Age of Island Nebulae

As telescopes improved through the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the number of mysterious fuzzy objects in the sky steadily increased. Astronomers catalogued them carefully, even when they could not explain what they were seeing. These objects did not behave like stars, nor did they resemble planets or comets. They appeared distant, diffuse, and strangely stubborn in revealing their true nature.

The word nebula was used generously. It described anything that looked cloudy through a telescope. Some nebulae clearly belonged to the Milky Way, such as glowing gas clouds where stars were being born. Others, however, were different. A few showed faint spiral structures. Others appeared as smooth, oval smudges of light. These forms sparked quiet speculation among astronomers who sensed they might be something else entirely.

By the late eighteenth century, a bold idea began to circulate. These unusual nebulae might be island universes, vast stellar systems floating far beyond the Milky Way. Each one, some suggested, could contain countless stars of its own, separated from us by unimaginable distances. It was a poetic and unsettling thought, and one that challenged the accepted cosmic order.

Most astronomers rejected the idea. There was no reliable way to measure distances on such scales, and without proof, the island universe theory remained little more than informed guesswork. The safer assumption was that all nebulae were part of the Milky Way, either as gas clouds or unresolved star clusters buried deep within it.

Still, the term island nebulae lingered in scientific writing, carrying with it a quiet sense of doubt. These objects did not fit comfortably into existing explanations. They waited patiently in the sky, unresolved and misunderstood, until better tools and sharper measurements could finally decide their fate.

The Milky Way as the Whole Universe

By the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the Milky Way had grown in astronomers’ minds from a beautiful feature of the sky into the defining structure of the cosmos. Star counts and early attempts at mapping suggested a vast, flattened system, large enough to contain everything visible through telescopes. Within this framework, it felt logical to assume that the universe and the Milky Way were one and the same.

Astronomers worked under severe limitations. Distances to stars were extraordinarily difficult to measure, and even the nearest stars showed only the faintest shifts against the background sky. Beyond those, depth vanished into uncertainty. Without reliable distance markers, scale became guesswork, and the Milky Way was imagined as an enormous stellar disk with the Sun positioned close to its centre.

This model comfortably absorbed the mysterious nebulae. If the Milky Way were large enough, then these hazy objects could easily be clouds of gas or clusters of unresolved stars embedded within it. Spiral nebulae were particularly puzzling, but many believed their shapes could be explained by local phenomena such as rotating gas clouds or star formation regions seen from a distance.

The idea that the Milky Way might be just one system among many was considered unnecessary and even extravagant. There was no compelling evidence to demand such a conclusion, and astronomy at the time favoured caution over speculation. The universe felt complete, bounded by the limits of the Milky Way’s stars.

Yet this confidence rested on fragile assumptions. The true size of the Milky Way had been overestimated, its structure imperfectly understood, and its centre misidentified. As observations improved, small inconsistencies began to surface, hinting that the familiar cosmic map might be drawn on a far smaller canvas than anyone realised.

The Great Debate of 1920

The growing unease over the true nature of nebulae finally surfaced in public in April 1920, during a formal debate at the Smithsonian Museum of Natural History in Washington, D.C. What later came to be known as the Great Debate placed the size of the universe itself under scrutiny.

At the heart of the discussion was a simple but explosive question. Were spiral nebulae part of the Milky Way, or were they separate stellar systems existing far beyond it?

One side argued that the Milky Way was immense, large enough to contain all known nebulae. Spiral forms, they claimed, were nearby objects, possibly young solar systems or gas clouds shaped by rotation. Supporting this view were observations of novae that appeared unusually bright, suggesting these nebulae were relatively close.

The opposing view challenged this assumption. It proposed that the Milky Way was only one galaxy among many, and that spiral nebulae were vast systems comparable in size to our own. This argument relied on indirect evidence, patterns in distribution, and the growing suspicion that the Milky Way had been vastly overestimated in scale.

The debate ended without resolution. Both sides presented compelling points, yet neither possessed the decisive measurement needed to settle the matter. No reliable method existed to determine distances on such extraordinary scales. The universe remained suspended between two possibilities, either comfortably contained or unimaginably vast.

What the Great Debate achieved was not an answer, but urgency. It made clear that astronomy had reached the limits of speculation. Only precise measurement, not argument, would reveal whether humanity lived in a solitary galaxy or in a universe crowded with countless others.

Edwin Hubble and the Measurement That Changed Everything

The stalemate left by the Great Debate did not last long. Within a few years, the question of the universe’s true scale would be settled, not through rhetoric, but through careful observation and measurement. The turning point came with the work of Edwin Hubble, working at the Mount Wilson Observatory in California.

Hubble had access to the Hooker Telescope, then the most powerful optical telescope in the world. Rather than arguing about the nature of nebulae, he focused on something more concrete. He searched for individual stars within spiral nebulae, specifically a rare class known as Cepheid variable stars. These stars brighten and dim at predictable rates, allowing astronomers to calculate their true luminosity and, crucially, their distance.

When Hubble identified Cepheid variables inside several spiral nebulae, including the Andromeda nebula, the results were startling. The calculated distances placed these objects far beyond the outer limits of the Milky Way, at scales no one could reasonably dismiss. They were not nearby clouds or minor structures within our galaxy. They were vast stellar systems in their own right.

The implication was unavoidable. The Milky Way was not the universe. It was one galaxy among many.

Hubble’s findings quietly but decisively ended the island nebula controversy. Almost overnight, the universe expanded in the scientific imagination. What had once been considered faint smudges within our galaxy were now understood as entire galaxies, each containing billions of stars.

Astronomy crossed a threshold. The cosmos was no longer singular and enclosed. It was vast, layered, and filled with worlds beyond counting.

The Death of Island Nebulae and the Birth of Galaxies

Hubble’s measurements left little room for compromise. Once distances were established beyond the limits of the Milky Way, the long-standing classification of spiral nebulae collapsed. These objects could no longer be treated as clouds or minor structures within our galaxy. They were something far larger and far more complex.

The term island nebulae slowly faded from scientific use. It had served as a placeholder for uncertainty, a name that acknowledged doubt without resolving it. Now it was clear that these islands were not drifting within the Milky Way at all. They were entire stellar systems, each one vast enough to rival or exceed our own.

A new word moved to the centre of astronomy. Galaxy. Derived from the Greek word for milk, it had once referred only to the Milky Way. After Hubble, it became a universal category. The Milky Way was no longer unique. It was one example in a growing population of galaxies scattered across the cosmos.

Acceptance did not arrive instantly. Some astronomers resisted the implications, unsettled by how radically the universe had expanded in scale. But the evidence was firm and repeatable. Additional observations confirmed Hubble’s results, and more galaxies were measured at even greater distances.

This shift transformed astronomy. Research moved beyond mapping a single system to understanding how galaxies formed, evolved, and interacted. The universe was no longer a closed structure with a single centre. It became an open expanse filled with countless galaxies, each carrying its own history.

What began as faint, misunderstood smudges of light had forced humanity to redraw the boundaries of existence itself.

Lesser-Known Galaxies Once Thought to Belong to the Milky Way

Beyond the famous examples, several lesser-known galaxies played a quiet but crucial role in dismantling the idea of a single galactic universe. These objects spent decades hiding in plain sight, mislabelled and misunderstood, before evidence finally set them free.

The Sombrero Galaxy offers one of the most striking cases. Early observers catalogued it as a peculiar nebula, drawn in by its bright core and sharp dust lane. Its unusual appearance made it difficult to classify. It did not resemble the elegant spirals astronomers were beginning to recognise, nor did it fit neatly into existing categories. Only later did detailed observations reveal its true nature as a massive galaxy with a dense central bulge and a supermassive black hole at its core. What once appeared as a local oddity turned out to be a distant and complex stellar system.

Barnard’s Galaxy, also known as NGC 6822, was long dismissed as a faint irregular cloud within the Milky Way. Its low brightness and scattered stars made it easy to overlook. Precise distance measurements eventually placed it well outside our galaxy, identifying it as a dwarf galaxy in its own right. Its importance lies not in its size, but in what it revealed. Galaxies did not need to be grand spirals to exist. Small, irregular systems were common and significant.

Messier 81 followed a similar path. Early astronomers recorded it as another nebula, assuming it belonged to the Milky Way. Later studies showed it to be a dominant spiral galaxy interacting gravitationally with its neighbours. This interaction provided early clues that galaxies influence each other over immense spans of time.

Together, these overlooked systems reinforced a simple truth. The Milky Way was not crowded with nebulae. It was surrounded by other galaxies.

A Universe That Suddenly Multiplied

The confirmation of galaxies beyond the Milky Way did more than settle a scientific argument. It fundamentally altered humanity’s sense of scale. What had once been a single cosmic system now fractured into countless independent worlds, each separated by distances so vast they defied everyday intuition.

Before this realisation, the universe felt finite and almost familiar. After it, the numbers became staggering. If the Milky Way was only one galaxy, then every confirmed spiral or elliptical object implied another immense system of stars. With each new observation, the universe did not merely grow larger. It multiplied.

This shift had an immediate psychological impact on astronomy. The Milky Way lost its privileged status as the centre of everything. The Sun became one star among billions, in one galaxy among many. The idea of a central cosmic vantage point quietly disappeared. There was no special location anymore, only perspective.

Astronomers also began to understand that galaxies were not rare exceptions scattered through empty space. They were the fundamental building blocks of the universe. Wherever telescopes looked deeply enough, galaxies appeared. Clusters of them gathered together, forming immense structures that stretched across unimaginable distances.

This multiplication forced a change in questions. Instead of asking what nebulae were, astronomers began asking how many galaxies existed, how they formed, and how they were distributed across space. The universe was no longer something to be mapped edge by edge. It was something to be sampled, studied, and interpreted statistically.

In expanding the universe outward, this discovery also turned inquiry inward. Humanity was no longer standing inside the whole. It was standing inside a fragment of something vastly larger.

Modern Telescopes, Ancient Light

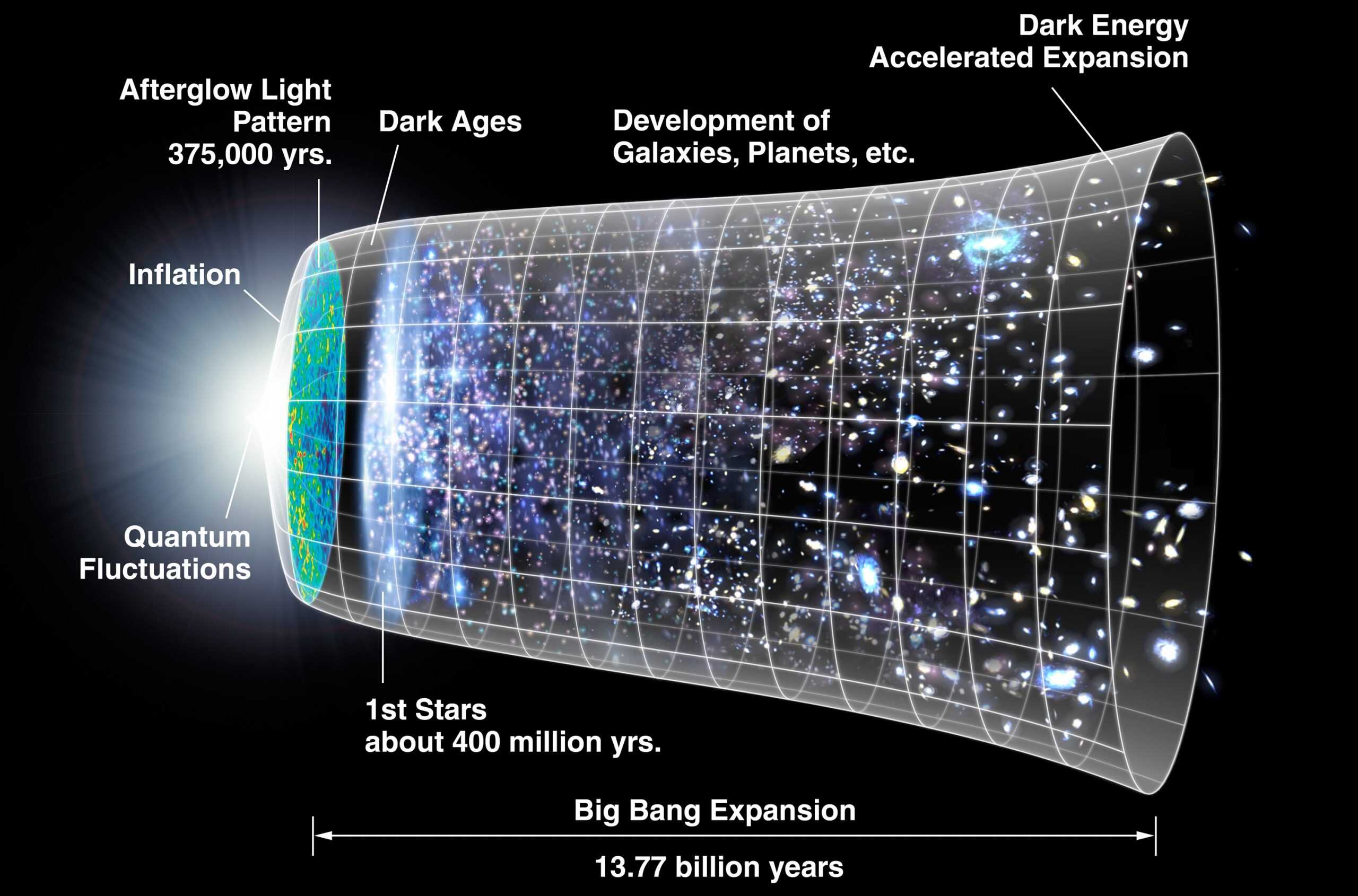

The modern understanding of galaxies is inseparable from the instruments that made them visible in unprecedented detail. As telescopes grew more powerful, they did more than sharpen images. They extended human vision across time itself.

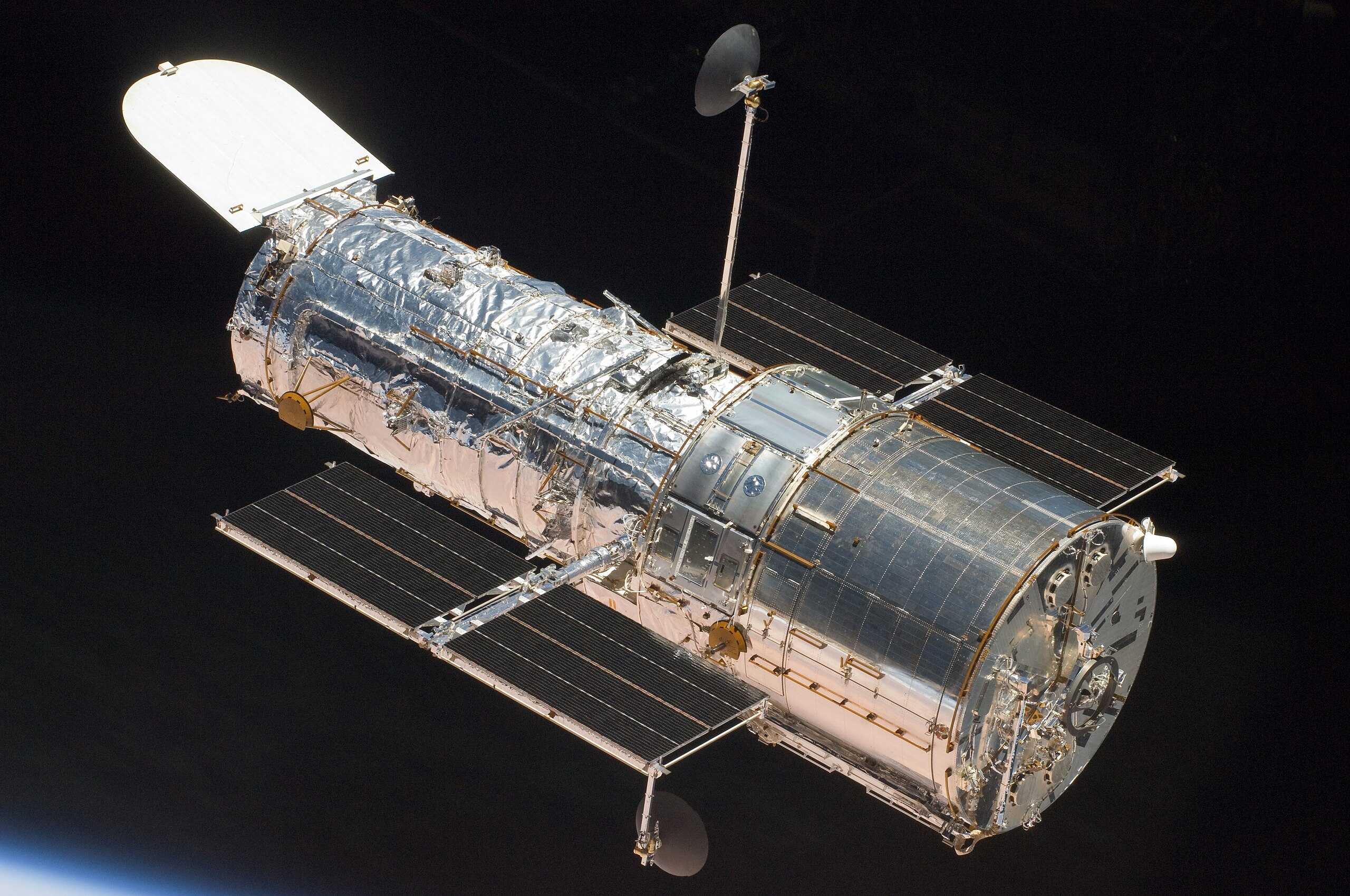

The Hubble Space Telescope marked a turning point. Free from atmospheric distortion, it revealed galaxies with extraordinary clarity and depth. Hubble showed astronomers that galaxies were not rare or evenly spaced curiosities. They filled the universe in staggering numbers. Its deep field images, capturing thousands of galaxies in what appeared to be empty patches of sky, quietly confirmed that the universe was richer and more crowded than previously imagined.

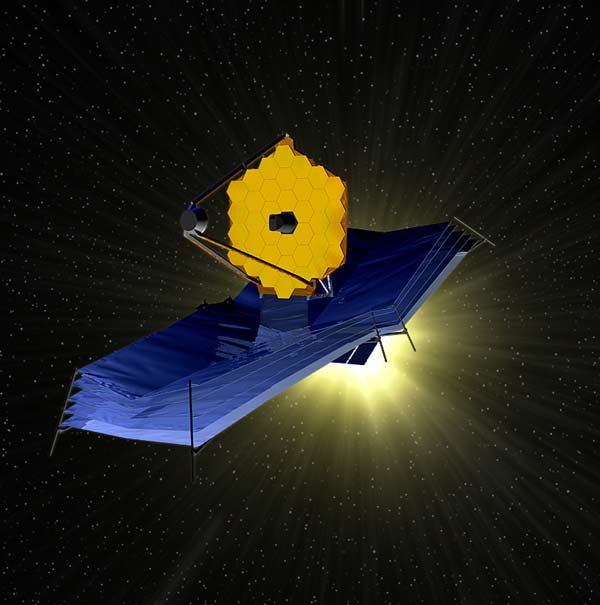

The James Webb Space Telescope pushed this understanding further back in time. Designed to observe infrared light, Webb peers through cosmic dust and reaches galaxies formed shortly after the universe began. Many of these early galaxies appear compact, irregular, and intensely active, offering direct evidence of how the first stellar systems assembled and evolved.

Other observatories expanded the picture beyond visible light. The Chandra X ray Observatory exposed violent galactic environments, revealing black holes feeding at the centres of galaxies and the energetic processes shaping them. Radio and infrared surveys added further layers, showing cold gas reservoirs and hidden star formation invisible to optical telescopes.

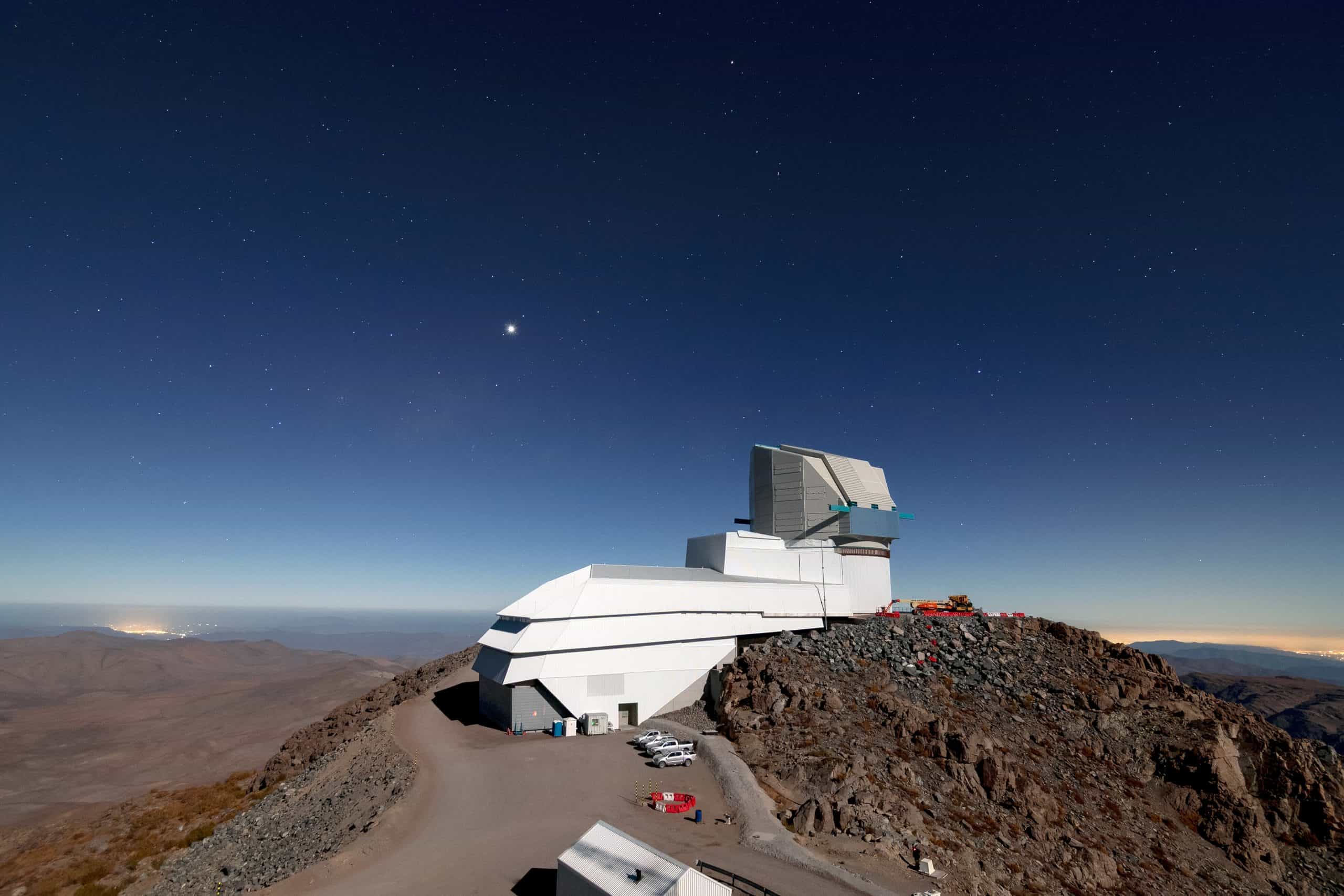

Soon, the Vera C Rubin Observatory will transform how galaxies are studied altogether. By repeatedly scanning the entire sky, it will track changes over time, capturing galaxy interactions, mergers, and subtle shifts that unfold across cosmic scales.

Together, these observatories confirm a profound truth. Every distant galaxy is a message sent across time. Modern telescopes do not merely observe space. They reconstruct the universe’s long and unfinished story.

Closing Reflection: The Sky That Changed Its Meaning

The night sky did not change when galaxies were discovered. The stars remained where they had always been, and the faint smudges of light still hovered at the edges of vision. What changed was understanding. The familiar canopy above Earth was no longer a ceiling. It became a doorway.

Where astronomers once saw a single stellar system, they now recognised a universe layered with depth, distance, and time. Each galaxy represented not a background detail, but a complete world of stars, history, and motion. The Milky Way shifted from being the whole story to being one chapter among many.

This transformation carried a quiet lesson. Knowledge does not simply add detail. It reshapes meaning. The sky that once felt small and comprehensible became vast and humbling, yet also richer and more alive. Humanity’s place within it grew smaller in scale, but larger in context.

The sky is still there, unchanged. But once you know what it truly holds, it can never look the same again.

Read More: Latest