North India’s rivers are more than waterways, they are sacred lifelines, where myths, legends, and living traditions shape journeys of faith, culture, and tourism.

Rivers have always been the lifeblood of North India. Flowing from the towering peaks of the Himalayas into the fertile plains, they nourish the land, shape civilisations, and inspire faith. For centuries, they have not only provided water for survival but also become symbols of divinity, carrying stories and legends that continue to live in the hearts of millions.

In this vast region, rivers like the Ganga, Yamuna, and Saraswati are more than just geographical features. They are sacred pathways, deeply woven into the cultural fabric of society. Each river is associated with myths that elevate it from a natural entity to a spiritual guide. These myths give the rivers a personality, making them revered deities rather than streams of water. Pilgrims travel to their banks not simply to see their beauty but to connect with their stories and the promises they hold.

As times have changed, rivers have also become a focal point for a new form of travel. River tourism is gaining momentum across North India. Travellers today seek more than sightseeing; they look for experiences that blend adventure, heritage, spirituality, and ecology. The Ganga offers thrilling rafting opportunities at Rishikesh, while the Yamuna takes visitors on a cultural journey through Mathura and Vrindavan. The invisible Saraswati draws those who are curious about its mythical presence at the confluence in Prayagraj.

What makes river tourism in North India unique is the way myths enhance the journey. A rafting trip down the Ganga feels different when one knows the story of its descent from heaven through the locks of Lord Shiva. A serene boat ride on the Yamuna becomes richer when paired with tales of Krishna’s childhood adventures on its banks. These myths transform travel into a layered experience, where history, legend, and nature meet.

The Sacred Geography of North Indian Rivers

The Ganga River

The Ganga is not only the most celebrated river of North India but also one of the most revered in the world. It originates from the icy glaciers of Gaumukh in Uttarakhand, where pilgrims trek to witness the point where the Bhagirathi stream begins. From there, it flows down into the plains, gathering strength and significance as it passes through ancient cities like Haridwar, Varanasi, and Prayagraj. Each of these places is tied to myths that make the Ganga a sacred symbol of purity and redemption.

According to Hindu mythology, the Ganga River descended from the heavens after the penance of King Bhagiratha, who prayed for her waters to cleanse the ashes of his ancestors and free them from the cycle of rebirth. It is believed that Lord Shiva captured the mighty river in his locks to soften her force before she touched the earth. This myth explains not only the Ganga’s divine origin but also why pilgrims view its waters as spiritually cleansing. To bathe in the Ganga River is to wash away sins, and to have one’s ashes immersed in its current is considered the path to liberation.

In modern times, the Ganga River has become a hub of river tourism. Haridwar and Rishikesh welcome thousands of visitors each year who attend the evening aarti ceremonies, where lamps float on the river and chants fill the air. Adventure seekers find thrill in rafting through the Ganga’s rapids, while spiritual seekers arrive to meditate on its peaceful banks. The combination of faith and fun makes the Ganga unique among world rivers.

The Ganga’s story is not just about water; it is about a living goddess who continues to inspire, heal, and attract people from across the globe.

The Yamuna River

The Yamuna River flows as both a river and a legend. Rising from the Yamunotri glacier in Uttarakhand, she begins her journey high in the Himalayas before winding her way through some of the most storied cities of North India. Unlike many rivers, the Yamuna River carries not only physical waters but also a treasury of myths that shape her identity in every region she touches.

Mythology describes the Yamuna as the daughter of the Sun God, Surya, and the sister of Yama, the God of Death. It is believed that a dip in her waters frees a devotee from the fear of death, granting both spiritual and earthly blessings. This association makes the Yamuna a river of compassion and deliverance, standing alongside her more famous sibling, the Ganga, as a goddess in her own right.

The Yamuna River is also inseparably tied to the life of Lord Krishna. In Mathura and Vrindavan, her banks are remembered as the setting for Krishna’s playful childhood tales. Stories speak of the young Krishna subduing the serpent Kaliya in the Yamuna’s depths, an act that symbolised the victory of good over evil. The river also features in the Rasleela, where Krishna danced with the gopis under the moonlight by her shimmering waters. These narratives make the Yamuna not only a sacred river but also a living backdrop to divine love and heroism.

For modern travellers, the Yamuna River offers both cultural and spiritual experiences. Pilgrims gather at Vrindavan’s ghats to perform rituals, while others visit Delhi and Agra, where the river flows past Mughal monuments like the Taj Mahal, adding to their romance and majesty. Despite challenges of pollution, the Yamuna remains a river of legends, deeply etched into the spiritual and cultural map of North India.

The Saraswati River

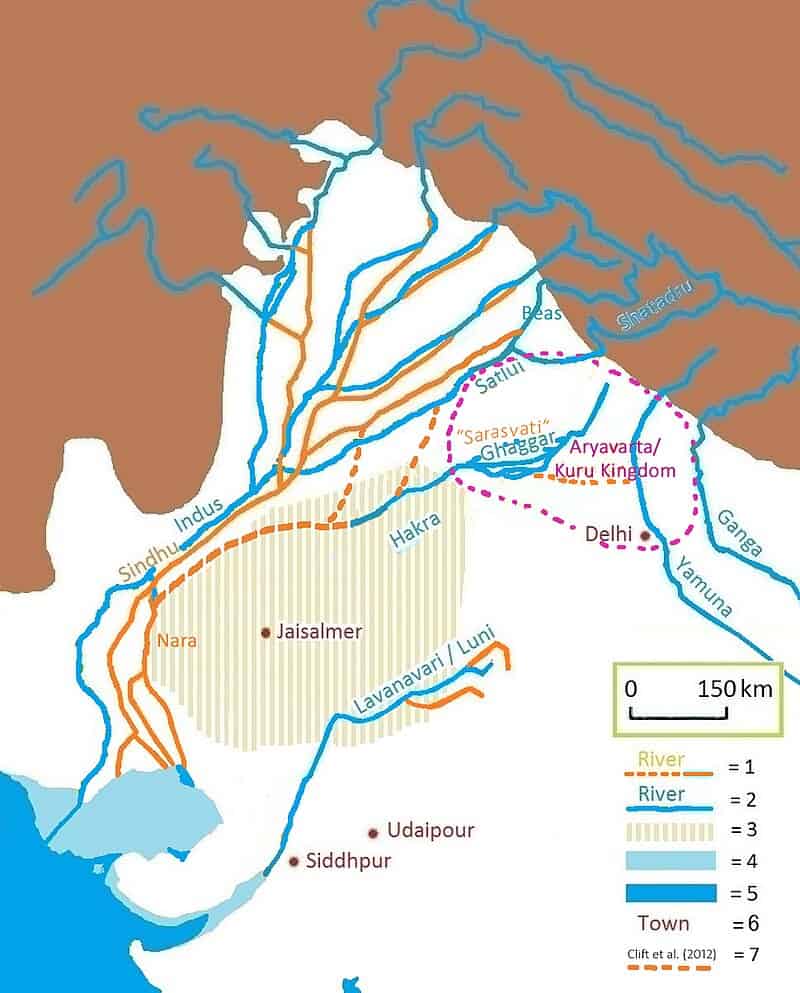

The Saraswati River is perhaps the most mysterious of North India’s rivers. Unlike the Ganga or the Yamuna Rivers, it does not flow visibly across the land today, yet its presence is felt strongly in the collective memory of Indian culture. Revered in the Rigveda as a mighty river that nourished early Vedic civilisation, the Saraswati River is often called the invisible river, believed to still flow underground. Its absence in physical form has only added to the aura of myth and legend that surrounds it.

Mythology tells us that the Saraswati River was born from the Himalayas and once flowed majestically alongside the Ganga and Yamuna Rivers. It is said to have disappeared beneath the earth due to a curse or a divine decision, though many devotees believe that its sacred waters still merge with those of the Ganga and Yamuna at the Triveni Sangam in Prayagraj. This unseen presence is why millions consider bathing at the confluence to be spiritually rewarding, as it symbolises union with three rivers, including one that belongs more to faith than geography.

The Saraswati River is also celebrated as the river of knowledge and wisdom. Its name is associated with the goddess Saraswati, the deity of learning, music, and art. In this form, the river becomes more than a physical entity; it represents a higher flow of intellect and creativity. Ancient texts describe rituals and sacrifices performed on its banks, linking it deeply with spiritual pursuits.

For travellers, Kurukshetra in Haryana is a key destination connected with the Saraswati River. Here, Saraswati Kund is worshipped as a sacred source, and many pilgrims visit during festivals. Even without visible waters, the river continues to attract those who seek to explore its myths, blending archaeology, spirituality, and folklore into one journey of discovery.

The Indus River

The Indus River, known in India as the Sindhu River, is one of the most historic rivers in the world. Rising in the high Tibetan Plateau near Lake Mansarovar, it enters India through the Union Territory of Ladakh, where it winds across dramatic valleys before flowing onwards into Pakistan. For millennia, it has stood as a cradle of civilisation, nourishing the ancient Indus Valley culture, and even today it continues to shape the identity of the regions it touches.

The Rigveda, one of the oldest scriptures, praises the Sindhu River as a mighty and roaring river. It was seen as a symbol of vitality and abundance, a force that blessed the land with fertility and strength. The very name “India” is rooted in the Indus, underlining how deeply it is tied to the subcontinent’s heritage and cultural identity.

Mythology describes the Indus as a river of cosmic power, embodying both physical might and spiritual continuity. Ancient hymns often portray it as a river blessed by the gods, one that bridged the human world with the divine. For the people of early Vedic times, it was more than water; it was the essence of prosperity and endurance.

In present-day Ladakh, the Indus River offers both spiritual and adventurous experiences. Its turquoise waters cut through stark mountain landscapes, creating vistas that draw travellers from across the world. River rafting near Leh has grown popular, while monasteries such as Thiksey and Hemis stand watch over its valley, adding a layer of serenity and cultural depth. Local festivals often celebrate the Indus as a lifeline in an otherwise rugged land.

The Indus remains both legend and lifeline. It is a river that has carried myths, sustained societies, and given its very name to a nation, holding an enduring place in the geography and imagination of North India.

The Tributary Rivers of North India

While the Ganga, Yamuna, Saraswati, and Indus Rivers command much of the spiritual and cultural attention, the tributary rivers of North India also play vital roles in shaping both landscape and legend. Rivers such as the Ghaghara, Gandak, Betwa, and Chambal enrich the heartland with stories and myths that add depth to their physical presence.

The Ghaghara River, also called the Karnali in Nepal, enters India through Uttar Pradesh. Locals often connect it with tales of ancient sages who meditated on its banks. Flowing through lush plains, it is celebrated as a source of fertility and abundance. Fishermen and farmers along its course depend on its life-giving waters, while pilgrims see it as an extension of the Ganga’s sanctity.

The Gandak River rises in the Himalayas and carries with it the aura of mountain purity. Flowing through Bihar and Uttar Pradesh, it is closely associated with Buddhist and Hindu traditions alike. Legends suggest that saints and monks once travelled along its banks, spreading knowledge and faith. Its swift current mirrors the vitality attributed to it in folklore.

The Betwa River, flowing through Madhya Pradesh and Uttar Pradesh, is remembered in connection with tales of loyalty and sacrifice. According to folklore, it is named after the sage Vetravati, who is believed to have performed penance by its banks. Today, the river winds past historic towns like Orchha, where palaces and temples overlook its waters, giving travellers a rare blend of heritage and myth.

The Chambal River carries perhaps the most unusual myth. Feared as a cursed river in ancient times, it was said to have been born of a pool of animal blood shed in a great battle. Because of this legend, its waters were avoided for centuries. Ironically, this very fear helped preserve its ecosystem, making the Chambal today one of the cleanest rivers in India and a sanctuary for gharials, dolphins, and migratory birds.

These tributaries may not always hold the same renown as the Ganga or Yamuna, but their myths and stories continue to weave them into the sacred geography of North India, offering travellers both natural beauty and cultural richness.

Adventure and Eco-Tourism

River tourism in North India has grown into an exciting blend of thrill and sustainability, attracting adventurers and eco-travellers alike. The Ganga River at Rishikesh is perhaps the most famous destination for white-water rafting in India. Its rapids, ranging from gentle stretches to heart-pounding torrents, draw both first-time rafters and seasoned professionals. Beyond rafting, kayaking, body surfing, and cliff jumping have also become part of the adventure scene, adding layers of excitement to a journey along this sacred river.

In Himachal Pradesh, the Beas and Sutlej rivers provide equally engaging experiences. Their courses through mountain valleys make them ideal for fishing and camping along the banks. Anglers often seek out mahseer fish in these waters, while eco-tourists are drawn to the pristine environment and opportunities for birdwatching. The crisp mountain air and flowing rivers create an atmosphere where the natural world feels untouched.

The Chambal River, with its haunting myth of cursed origins, has emerged as a surprising eco-tourism hotspot. Today it is one of the cleanest rivers in India, hosting the National Chambal Sanctuary. Here, travellers can embark on boat safaris to spot the critically endangered gharials, along with freshwater dolphins, turtles, and migratory birds. The very myth that once kept people away has ensured that this river’s ecosystem has remained relatively unspoiled.

Adventure and eco-tourism along rivers in North India are not only about adrenaline but also about balance. They allow travellers to experience the raw force of nature while appreciating the need to protect fragile river systems. The fusion of myth and adventure makes every rafting trip or wildlife safari more than a holiday. It becomes a story — one that connects the traveller with rivers as living, breathing entities.

Spiritual and Pilgrimage Tourism

The Ganga River and Pilgrimage

The Ganga River is the most important river for pilgrimage in North India. At Haridwar, Rishikesh, and Varanasi, devotees come to bathe in her waters, believing that a single dip removes sins and grants liberation. The evening Ganga Aarti at Haridwar and Varanasi is one of the most moving rituals in India: priests perform coordinated prayers with lamps, conch shells, and chants, while thousands of pilgrims float earthen lamps on the river. Ash immersion ceremonies at Varanasi’s Manikarnika and Harishchandra ghats draw families who believe the Ganga carries the departed to salvation. These rituals are not simply symbolic but represent the deep connection between the river and human destiny.

The Yamuna and Krishna Devotion

The Yamuna River is inseparably linked with Lord Krishna. In Mathura and Vrindavan, her banks are associated with Krishna’s playful childhood and divine love. Devotees recall the legend of Krishna subduing the serpent Kaliya in the Yamuna’s depths, a victory that symbolises protection and grace. Pilgrims throng the ghats during Janmashtami and Holi, where the Yamuna becomes central to celebrations filled with colour and music. The Yamuna Aarti in Vrindavan is smaller than the Ganga’s but intimate and powerful, with songs dedicated to Krishna’s bond with the river. For travellers, it is not only a religious act but also an immersion in stories that shape the cultural fabric of Braj Bhoomi.

The Saraswati and the Sangam

Although invisible, the Saraswati River holds a vital role in pilgrimage through the Triveni Sangam at Prayagraj. Here, it is believed that the Ganga, Yamuna, and Saraswati meet, creating one of Hinduism’s holiest confluences. Pilgrims flock to bathe in these waters during festivals, convinced that the hidden Saraswati’s presence multiplies the sanctity of the ritual. The belief in Saraswati’s underground flow lends the site a mystical aura, turning every dip into a union with both visible and unseen divinity. The rituals here show how myth extends the power of faith beyond geography, drawing millions each year.

The Kumbh Mela

The Kumbh Mela is the pinnacle of river pilgrimage. Held in rotation at Haridwar, Prayagraj, Ujjain, and Nashik, it transforms Prayagraj’s Sangam (merging of two rivers) into the largest human gathering on earth. Every twelve years, millions assemble to take the shahi snan, or royal bath, on auspicious dates calculated by astrology. Saints, sadhus, pilgrims, and tourists all join in this mass ritual, believing it ensures moksha, or release from rebirth. The sight of naga sadhus leading the procession into the river is unforgettable, blending ancient traditions with living devotion. The scale of the Mela highlights not only spiritual power but also the continuing importance of rivers as spaces where faith, myth, and community converge.

Cultural and Heritage Tourism

The Ghats and Riverfront Traditions

The ghats of North India form the cultural heart of river tourism. Nowhere is this more evident than in Varanasi, where over 80 ghats line the Ganga River. Each has a distinct identity: Dashashwamedh Ghat is known for its grand aarti ceremonies, Manikarnika Ghat for cremations, and Assi Ghat for meditation and yoga.

These riverfront steps are not simply physical spaces but stages where history, ritual, and everyday life come together. Pilgrims bathe, students study, and sadhus chant, all against the backdrop of timeless waters. The ghats at Haridwar, particularly Har Ki Pauri, serve a similar role, bringing communities together for spiritual rituals and festivals. For travellers, these ghats provide a living museum of India’s culture, blending devotion with daily rhythms.

Mughal and Architectural Heritage along Rivers

Rivers in North India also shaped the course of architectural history. The Yamuna River, in particular, flows past some of the world’s most celebrated monuments, including the Taj Mahal in Agra, which was deliberately built on its banks to symbolise eternal love reflected in the water. Delhi’s Mughal gardens and riverfront structures highlight how rulers used the Yamuna as a source of beauty and sustenance. Further upstream, forts such as Orchha on the Betwa stand as examples of medieval rulers integrating rivers into their defence and cultural life. For visitors, these sites show how rivers were not only worshipped but also woven into the power and artistry of empires.

Festivals and Folk Traditions

Rivers are central to festivals and cultural expressions across North India. Chhath Puja, celebrated primarily in Bihar and Uttar Pradesh, is devoted to the Sun God and takes place exclusively on riverbanks, where devotees stand in waist-deep water offering prayers at sunrise and sunset. In Braj Bhoomi, Holi along the Yamuna becomes a theatrical celebration, with the river itself as a backdrop for Krishna’s stories. Local fairs along rivers, such as those at Allahabad during Magh Mela, mix spirituality with folk performance, showcasing music, dance, and theatre. For travellers, these festivals are an opportunity to see how rivers animate communities, turning natural landscapes into vibrant spaces of shared heritage.

Myths and Legends Shaping the Tourism Narrative

The rivers of North India are not defined by geography alone; they are transformed by the myths that flow with them, turning every journey into a pilgrimage of the imagination. The Ganga is believed to have descended from the heavens through the matted locks of Lord Shiva, answering King Bhagiratha’s penance to liberate his ancestors. This story elevates the river into a living goddess whose waters purify sins and guide souls towards liberation. Travellers who raft her rapids at Rishikesh or attend the aarti at Varanasi find themselves caught not only in the rhythm of the current but also in the timeless belief that the river carries the promise of redemption.

The Yamuna is equally bound to legend, particularly in the stories of Krishna. Her waters are celebrated as the stage for Krishna’s playful childhood, where he subdued the serpent Kaliya and danced with the gopis. For pilgrims in Mathura and Vrindavan, the Yamuna is more than water; she is a companion of divinity, embodying both love and deliverance.

At the Triveni Sangam, faith reaches its peak with the invisible Saraswati. Though unseen, her presence at the confluence with the Ganga and Yamuna makes the site one of the most sacred in Hindu belief. Millions who gather during the Kumbh Mela enter these waters convinced that Saraswati flows beneath, multiplying the sanctity of their ritual bath.

The Indus, praised in the Rigveda as mighty and eternal, carries its own aura of myth. Seen as a cosmic river, it symbolises power, continuity, and vitality, a force so enduring that the very name “India” is drawn from it. For travellers in Ladakh, the turquoise waters of the Sindhu are not simply landscapes of beauty but reminders of a civilisation that revered rivers as divine.

Together, these myths enrich river tourism by turning landscapes into legends. They remind every traveller that in North India, rivers are never only physical streams but eternal beings, shaping journeys through both faith and story.

Socio-Economic and Cultural Impact

River tourism in North India has become more than a cultural or spiritual journey; it is now a driver of local economies and a tool for preserving heritage. Pilgrims, tourists, and adventure seekers together create a steady stream of activity that sustains communities along riverbanks, generating employment and business opportunities for boatmen, priests, hoteliers, artisans, and guides. At Varanasi, for example, thousands of livelihoods are directly tied to services offered on the ghats, from boat rides at dawn to stalls selling offerings for rituals.

The rise of river cruises has also reshaped economic possibilities. Luxury cruises along the Ganga River now connect heritage towns, offering curated experiences that blend local cuisine, performances, and temple visits. These floating hotels attract international visitors, providing revenue for both hospitality operators and the smaller economies that serve them. The push for riverfront development in cities like Prayagraj and Haridwar highlights how tourism can revive infrastructure while showcasing cultural identity.

Culturally, river tourism preserves and promotes living traditions. Festivals such as Chhath Puja or the Kumbh Mela, centred on rivers, not only reaffirm faith but also serve as global cultural spectacles. They introduce folk music, dance, craft, and cuisine to a wider audience, ensuring that traditions thrive even in modern times. The mythological narratives tied to rivers also find renewed expression through storytelling, performances, and guided tours, keeping oral heritage alive for younger generations and international travellers alike.

At the same time, the socio-economic impact extends to environmental awareness. Clean-up campaigns and conservation projects, often supported by tourism stakeholders, highlight the need to balance growth with sustainability. Tourists who experience the rivers also return as advocates for their protection, showing how economic, cultural, and ecological threads are intertwined in the story of river tourism.

Read More: Latest