A global journey into the vibrant world of coral reefs and the fragile beauty that sustains our seas.

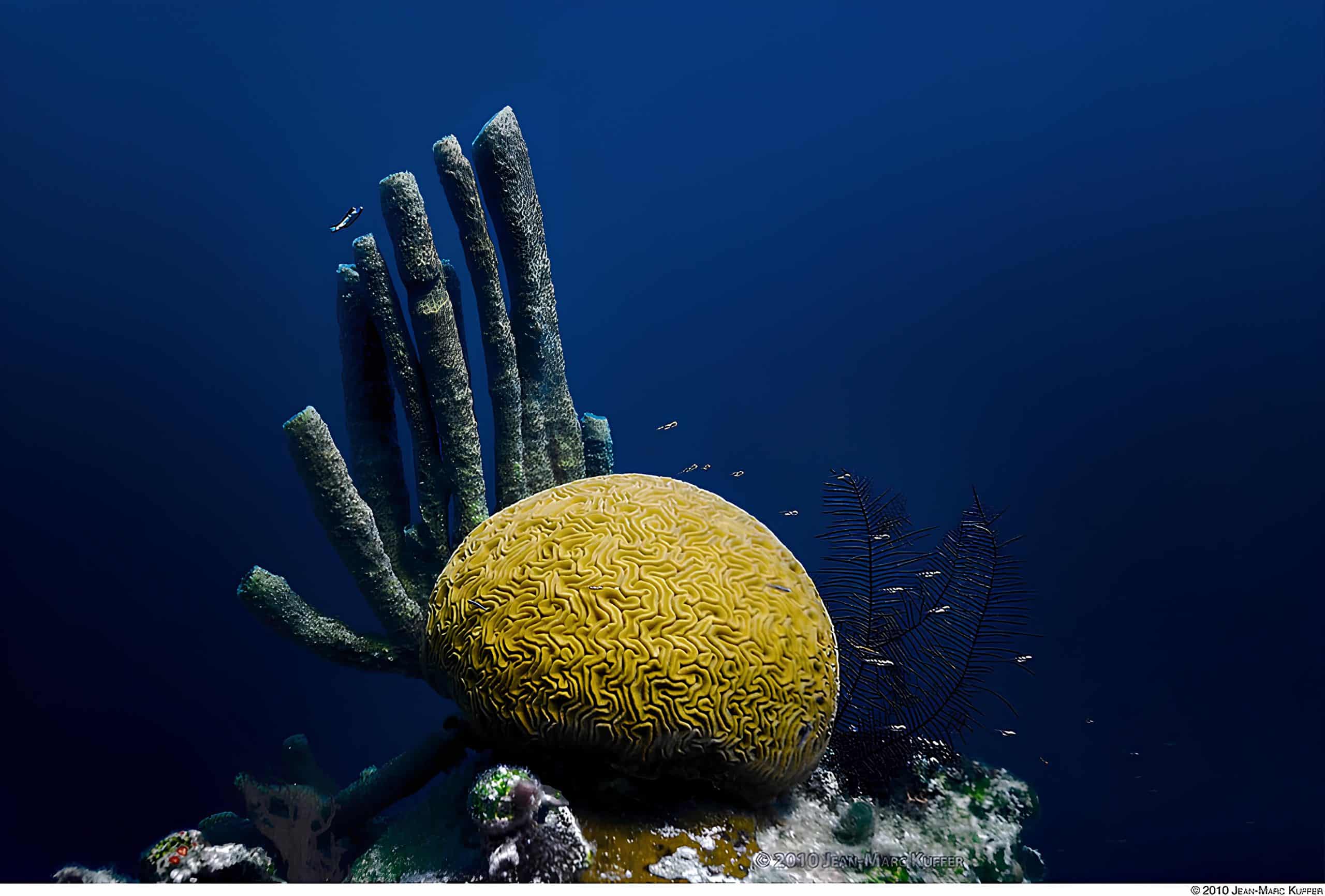

Coral reefs are the most dazzling ecosystems on our planet. They are living structures that rise slowly from the sea floor, grow through the combined labour of millions of tiny coral polyps, and shelter a universe of colour, motion and life. For centuries, these underwater cities have shaped the character of coastlines and the rhythm of marine cultures. They support fisheries that feed millions, sustain coastal communities, protect fragile shores from storms and supply a wealth of biodiversity that science is still trying to understand.

Today, coral reefs cover less than one percent of the ocean floor, yet they host nearly a quarter of all marine species. Their influence is far greater than their size suggests. They moderate the chemistry of the seas, nurture endangered creatures and form the backbone of marine food chains. They also hold cultural meaning for communities that have lived beside the water since time immemorial. Polynesian navigators, Andamanese tribes, fishermen in Lakshadweep and coastal families in the Caribbean all share one truth. Where the reefs flourish, life flourishes.

This story is a journey through the world’s great coral regions. Some lie in warm lagoons, some along volcanic ridges and others in fast-moving currents filled with shoals of bright fish. Together, they form the living jewels of the sea.

Coral Reefs of the Pacific: Vast, Ancient and Diverse

The Pacific is the world’s largest ocean and the birthplace of many great coral systems. It contains some of the oldest reefs ever discovered and some of the most biologically rich waters on Earth. Within this vast blue realm, reefs grow on volcanic slopes, shallow banks, narrow shelves and deep lagoons. Each region reveals its own rhythm and colour palette.

The Great Barrier Reef in Australia

Stretching for more than two thousand kilometres along the coast of Queensland, the Great Barrier Reef is often described as the largest living structure on Earth. Its reefs, islands and shoals are home to an extraordinary collection of marine life. Giant clams open their iridescent mantles to the sun. Manta rays glide through channels like celestial wings in motion. Green turtles rest in sheltered coves. Countless fish species flit between branching corals in bursts of yellow, blue and silver.

The reef has faced repeated bleaching events triggered by warmer waters. Scientists have mapped these changes and worked with local communities to identify resilient coral species. Some reefs show slow signs of recovery, while others remain vulnerable. Despite these challenges, the Great Barrier Reef continues to be an iconic symbol of nature’s power and fragility.

The Coral Triangle

The Coral Triangle, which spans Indonesia, the Philippines, Malaysia, Timor Leste, Papua New Guinea and the Solomon Islands, holds the richest marine diversity anywhere on Earth. This region contains more than five hundred coral species and thousands of fish species. It is often called the global centre of marine life.

Small fishing villages, coastal markets and indigenous communities depend on these reefs for food, livelihood and cultural identity. Traditional fishing techniques, reef taboos, seasonal bans and local marine parks have protected these waters for generations. In recent decades, community-led conservation areas have been created to preserve spawning sites, nursery grounds and fragile coral slopes.

Fiji, French Polynesia and Hawaii

Further east lies the island world of the central Pacific. Fiji is known as the soft coral capital of the world. Its reefs explode with colour that resembles gardens in perpetual bloom. Large bommies rise from the sea floor, covered in purple and pink soft corals that sway with the tide.

In French Polynesia, coral reefs are tied to legends, rituals and the deep ancestral knowledge of ocean navigation. The reef is a cultural companion rather than a simple ecosystem. Hawaii adds its own character with volcanic slopes, black lava outcrops and a network of shallow reefs where monk seals, butterflyfish and turtles thrive.

Rising sea levels and ocean acidification remain a concern across this region. Scientists are studying how these changes affect reef building and the behaviour of marine species that rely on coral habitats.

The Indian Ocean and Bay of Bengal: Volcanic Chains, Sheltered Lagoons and Ancient Reefs

This part of the world is shaped by island arcs, deep trenches, monsoon cycles and long corridors of warm water that circulate between South Asia and Southeast Asia. Its reefs support both large marine creatures and delicate coral gardens.

Andaman and Nicobar Islands

Sitting between the Bay of Bengal and the Andaman Sea, the Andaman and Nicobar Islands are part of an ancient volcanic chain that rises out of deep blue water. Their coral reefs form a transition zone within the broader Indo-Pacific reef system.

Havelock, Neil and Cinque Islands are ringed with coral gardens that attract reef sharks, turtles, Napoleon wrasse, angelfish and schools of barracuda. The Mahatma Gandhi Marine National Park protects several islands and coral patches that are vital for breeding and recovery. Soft corals, gorgonian fans and sea whips add spectacle to the seascape.

The reefs face pressure from bleaching, pollution, uncontrolled visitor activity and sediment that washes in during storms. Conservation teams, research groups and trained divers have begun coral restoration projects. Coral nurseries and transplantation programmes are now active in several islands. Local communities and tourism operators are gradually adopting sustainable practices, including waste reduction and anchored mooring buoys that prevent damage to the reef.

The Maldives

Southwest of India lies the Maldives, a chain of ring-shaped atolls formed over submerged volcanoes. Sheltered by outer reefs and deep lagoons, these islands contain some of the clearest waters in the world.

The reefs support manta cleaning stations, turtle nesting grounds and an abundance of reef fish. The Maldives has become a symbol of both luxury tourism and climate vulnerability. Rising sea levels and repeated bleaching events have threatened shallow reefs. At the same time, coral regeneration initiatives led by marine biologists and local islanders are helping selected reefs recover through coral nurseries and conservation zones.

Seychelles, Mauritius and the Chagos Archipelago

Across the western Indian Ocean, the islands of Seychelles and Mauritius hold reefs that often lie within protected lagoons. In several regions, these reefs show remarkable natural resilience. The Chagos Archipelago contains some of the healthiest coral systems ever documented, mainly because of strict marine protected areas and minimal human disturbance.

These sites offer vital insights into what coral reefs could look like when human impact is low and ocean conditions remain stable. Research teams frequently use the region as a natural laboratory to understand which coral species can withstand warmer seas.

The Arabian Sea: Western Indian Waters and Lagoon Rich Atolls

Lakshadweep

On the other side of the Indian subcontinent lies Lakshadweep, a chain of coral atolls in the Arabian Sea. These islands are remarkably different from the Andaman group. Lakshadweep’s lagoons are shallow, bright and calm, with water that glows a clear shade of turquoise.

The corals frame islands like Agatti, Kadmat, Kavaratti and Bangaram. Their reefs are home to black tip sharks, parrotfish, snappers, surgeonfish and large schools of colourful reef dwellers. Lakshadweep has endured multiple bleaching events, yet several reef patches show natural recovery due to strong tidal flushing and sustainable fishing traditions that have lasted for centuries.

Local communities play a major role in conservation. Many families follow fishing practices that avoid damage to the coral. Youth groups participate in reef clean-ups and research programmes. With careful management, Lakshadweep’s reefs have the potential to become a model of community-based reef protection.

The Red Sea: Heat Resilient Reef Systems

The Red Sea contains some of the most naturally heat-resilient corals anywhere in the world. These reefs thrive in waters that are warmer and saltier than most tropical regions. Scientists believe they may hold the key to understanding how corals can adapt to rising global temperatures.

Egypt, Saudi Arabia and Sudan have become popular destinations for divers seeking dramatic drop-offs, rich coral walls and clear visibility. Despite increasing tourism, several parts of the Red Sea have maintained strong reef health due to strict coastal regulations, controlled diving zones and careful waste management.

The Caribbean: Beauty, Decline and Revival

The Caribbean Sea contains a different style of coral environment. Its waters hold fewer coral species than the Indo-Pacific, yet they host unique creatures and strong ecological relationships.

The Belize Barrier Reef, one of the largest reef systems in the Northern Hemisphere, supports manatees, nurse sharks, stingrays and colourful reef fish. The Bahamas and Cayman Islands contain patch reefs, coral heads and shallow gardens that attract snorkellers from around the world.

However, the Caribbean has faced decades of challenges. Overfishing, hurricanes, coral diseases and an invasive lionfish population have damaged many reefs. In response, organisations and volunteers have established coral nurseries. Young corals are grown in underwater frames and later replanted on degraded reefs. Divers also help remove lionfish to reduce pressure on local species. These efforts have shown early signs of success in several islands.

Life Within the Reef: A Universe of Colour and Movement

A coral reef is never still. Every hour brings new movement. Wrasses glide through channels in search of food. Groupers lurk near coral heads. Butterflyfish pair up and patrol their feeding grounds. Clownfish shelter within the tentacles of anemones. Each species has a role in maintaining the balance of the reef.

Migratory creatures also depend on these ecosystems. Turtles return to familiar feeding grounds year after year. Sharks use reefs as nurseries where juveniles can avoid predators. Rays follow plankton-rich currents that pass along reef slopes.

Reefs are connected to seagrass beds and mangrove forests. Juvenile fish often begin life in the shelter of mangrove roots, move to seagrass meadows as they grow, and then venture out to coral reefs as adults. This web of habitats is essential for a healthy coastline.

When the sun sets, reef life changes character. Nocturnal hunters emerge, and tiny bioluminescent organisms light up the water in flickers of green and blue. The reef becomes a different world where predators move silently and plankton clouds rise from the deep.

Threats Facing Coral Reefs Worldwide

Coral reefs are under pressure on a global scale. Increasing sea temperatures cause bleaching, which occurs when corals lose their symbiotic algae. Without these algae, corals weaken and may die if temperatures do not stabilise. Mass bleaching events have been recorded across the Pacific, the Indian Ocean and the Caribbean.

Ocean acidification, caused by higher carbon dioxide levels, reduces a coral’s ability to build its skeleton. Pollution from sewage, wastewater, mining and coastal development introduces chemicals and sediments that smother coral. Plastic waste tangles around reefs and blocks sunlight.

Overfishing disrupts the balance of reef communities. Destructive practices like dynamite fishing, cyanide fishing, and unregulated trawling have destroyed large parts of some reef systems. Unsustainable tourism also adds pressure. Anchors break coral branches. Poor snorkelling etiquette damages fragile structures. Several commercial sunscreens contain chemicals that harm coral larvae.

Scientific assessments indicate that the world has already lost a significant portion of its shallow reefs. Many regions now depend on urgent conservation and climate action.

Conservation, Innovation and Hope

Despite the challenges, coral reefs remain incredibly resilient. Many recover when conditions improve. Around the world, communities, researchers and conservation groups are working to protect and restore these ecosystems.

Marine Protected Areas

Countries have created marine parks and sanctuaries where fishing, development and tourism are controlled. Several UNESCO World Heritage sites preserve vital reef regions and monitor long-term ecological change. New technologies, including satellite surveillance and underwater robotics, assist researchers in tracking reef health on a global scale.

Community and Indigenous Leadership

In many parts of the Pacific, traditional reef guardianship is still practised. Village elders enforce seasonal bans, no-take zones and cultural rules that protect spawning sites. In the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, conservation groups collaborate with local residents to manage waste, protect fragile coral patches and restore damaged zones. In Lakshadweep, fishermen follow selective techniques that avoid harming reef structures.

These community-led efforts often succeed where external regulation struggles, because people protect what they depend on.

Scientific Interventions

Scientists have developed coral gardening techniques where fragments are grown in underwater nurseries. Once they reach a suitable size, they are transplanted to damaged reefs. Micro-fragmentation accelerates coral growth by dividing corals into small sections that heal quickly.

Researchers are also studying heat-tolerant coral species to understand how reefs can adapt to warming oceans. Assisted evolution experiments and genetic studies offer insights into long-term resilience.

Facts to Know: How Coral Reefs Are Born

Coral reefs begin with coral polyps, which are tiny animals that build hard limestone skeletons around themselves. These polyps live together in vast colonies, slowly creating the structures that form the foundation of reefs. Inside their tissues live microscopic algae that supply most of their energy through photosynthesis, a partnership that allows corals to grow in nutrient-poor waters. Corals need warm seas, clear sunlight and calm conditions to survive, which is why they flourish in tropical regions.

Reef systems take thousands of years to form, and their growth is both slow and delicate. Fringing reefs develop close to shore, while barrier reefs grow farther out at sea. Patch reefs arise in clusters across sandy or rocky bottoms, and atolls form circular structures that enclose bright, shallow lagoons. The pace of reef formation is so gradual that sudden changes in temperature, pollution or acidity can unsettle the balance that corals depend on, making them sensitive indicators of ocean health.

A Planet’s Colour at Stake

Coral reefs are among the most beautiful and meaningful environments on Earth. They are symbols of resilience, yet they are also reminders of how vulnerable life can be. Their survival depends on decisions made at every level, from global climate policy to the behaviour of a snorkeller dropping into a lagoon.

To protect coral reefs is to protect our coastlines, our fisheries, our cultures and our shared planet. The colour of the ocean is at stake, and the responsibility rests with all of us.

Read More: Latest