UNESCO-recognised traditional food cultures preserve identity, community bonds, and sustainable food heritage worldwide.

Here are 13 UNESCO-recognised culinary traditions worldwide, celebrating traditional food that embody cultural identity, communal heritage, and sustainable practices, while preserving time-honoured cooking techniques passed down through generations across diverse regions.

Washoku (Japan)

More than just a repertoire of delicious dishes, the traditional food culture of washoku embodies a holistic approach to food that harmonises nutrition, aesthetics, seasonal awareness, and deep-rooted respect for nature.

Washoku literally means “Japanese food” (“wa” for Japan and “shoku” for food or eating) and is recognised for its meticulous attention to the quality and freshness of ingredients. Stemming from Japan’s varied geography, which spans rich coastlines, mountain ranges, and fertile farmlands, the cuisine champions local, seasonal ingredients. Traditional japanese food meals reflect and honour the changing seasons, with plates often adorned with seasonal leaves or flowers.

At the core of everyday washoku is the Ichiju Sansai (“one soup, three sides”) structure: a nutritionally balanced combination of rice, soup (often miso), a protein, and two vegetable-based sides. This approach provides a satisfying nutritional variety while keeping fats minimal, contributing to Japan’s reputation for longevity and good health.

Washoku is also an essential part of Japanese life and celebrations. Special dishes, like the ornate osechi ryori for New Year’s, mark festivals and family milestones, fostering strong intergenerational bonds. Sharing meals is seen as an act of gratitude: before eating, diners say “itadaki-mas” expressing thanks to nature and the cook.

Borscht Cooking:

On July 1, 2022, UNESCO inscribed the Traditional food culture around the cooking of Ukrainian borscht on its List of Intangible Cultural Heritage in Need of Immediate Protection

Borscht is a vibrant, ruby-red dish woven into the very fabric of Ukrainian cultural life. Made primarily from beetroot and often enriched with cabbage, potatoes, carrots, onions, and sometimes meat, borscht varies from region to region and even from one family to another. Each recipe is steeped in local ingredients and the stories of those who prepare it. The process of cooking borscht is typically communal, involving multiple generations gathering in kitchens and around tables, especially during holidays, weddings, funerals, and key community celebrations.

Beyond its role at the dining table,this traditional food has become a symbol of unity, perseverance, and cultural pride amidst turbulent periods in Ukraine’s history. During the current conflict, the act of preparing and sharing borscht has taken on new dimensions, strengthening bonds and fostering hope. UNESCO’s recognition underscores this point: by protecting borscht, the world honours an “element of social integration and cohesion,” important not only during ordinary times, but also during armed conflict and emergencies (as noted by the Ukrainian Ministry of Culture).

Singaporean Hawker Culture

The origins of Singapore’s hawker culture reach back to the 1800s, when migrants from China, India, Malaysia, Indonesia, and beyond brought their culinary traditions to the island as street hawkers. These early food vendors, often moving through neighbourhoods with portable kitchens, adapted their homeland dishes to new ingredients and local preferences, creating the diverse cuisine now synonymous with Singapore.

For much of the 20th century, hawkers operated mostly on city streets, providing affordable, home-style food to workers and families. Image courtesy: Mohamad Hafiz via unesco.org

For much of the 20th century, hawkers operated mostly on city streets, providing affordable, home-style food to workers and families. However, as public health and city planning concerns grew, the government began to relocate hawkers into purpose-built hawker centres beginning in the late 1960s and 1970s.

This move created regulated communal dining halls, now more than 110 across Singapore, preserving food traditions in a cleaner and safer environment. Each centre serves as a neighbourhood hub where people of all races, ages, and backgrounds gather daily, sharing meals and stories.

Hawker culture holds a unique place as Singapore’s first UNESCO-recognised cultural tradition and is considered by locals as the “culinary soul” of the nation. More than half of today’s hawkers are second or third generation, carrying on and innovating family recipes amid changing tastes and lifestyles. However, with an average hawker age nearing 60, concerns about passing on these crafts to younger generations have spurred government-backed apprenticeship and succession programs, including the Hawkers’ Development Programme and the launch of an 18-day citywide HawkerFest after UNESCO’s inscription.

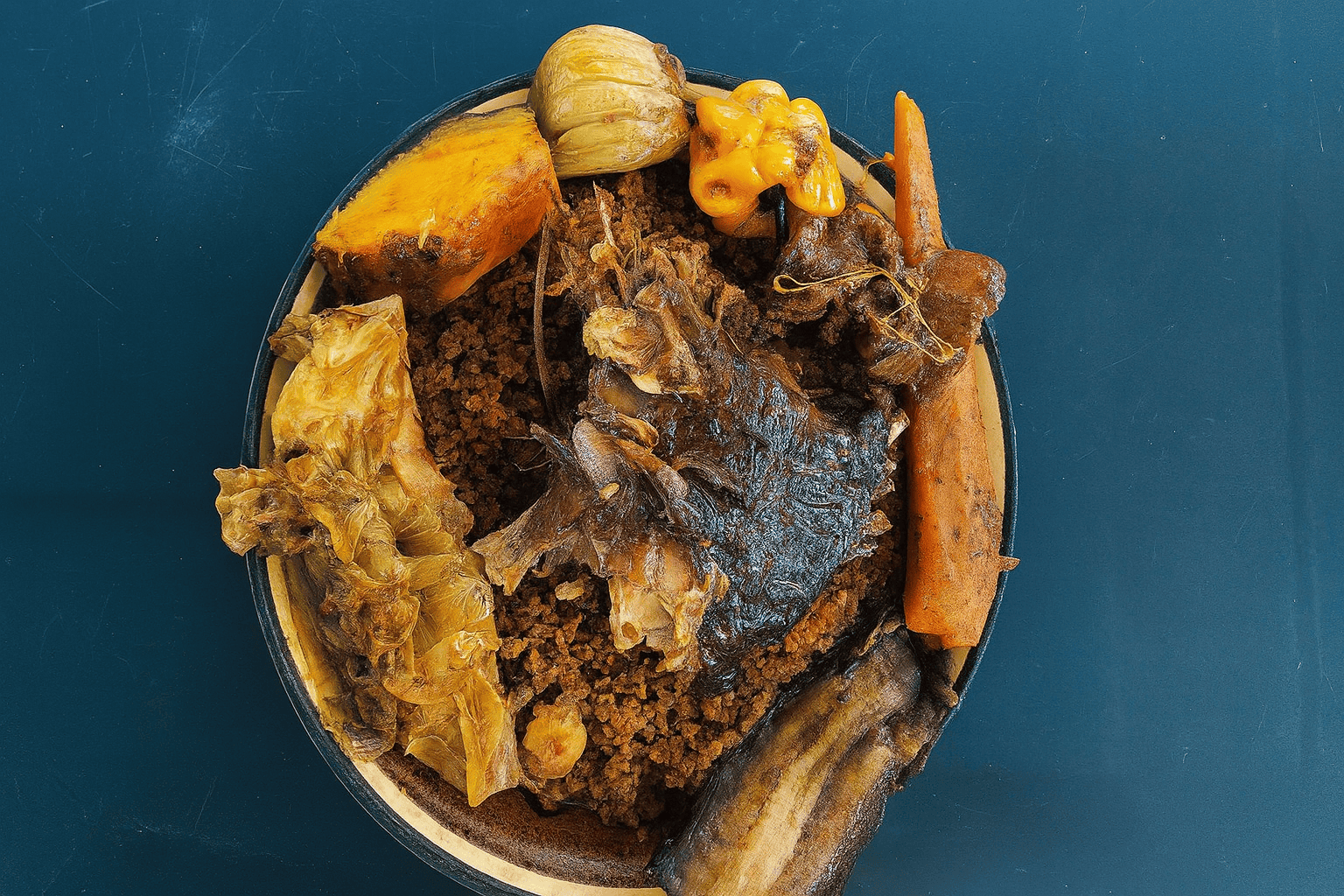

Ceebu Jën (Senegal)

Originating from the fishing communities of the island of Saint-Louis in northern Senegal during the 19th century, the dish is traditionally made with fresh fish (such as grouper or snapper), broken rice, and a variety of seasonal vegetables, including tomatoes, carrots, cabbage, cassava, and eggplant.

Historically, this dish is credited to a 19th-century Senegalese cook named Penda Mbaye, who was said to serve the dish in the governor’s residence during French colonial times in Saint-Louis. This richly flavoured food reflects a blend of indigenous culinary techniques and colonial influences, evolving over time into a complex composition celebrated across Senegal.

The recipe and cooking techniques are traditionally passed down orally within families, often from mother to daughter. It is typically served in a shared bowl, symbolising hospitality, social bonds, and community identity. Unique dining etiquette surrounds it, such as holding the bowl with the left hand and avoiding dropping grains of rice.

Interestingly, Ceebu Jën is recognised as the precursor to the famous West African Jollof rice, fueling regional food debates known as the “Jollof rice wars” about the dish’s origin and variations across countries like Ghana and Nigeria.

Joumou Soup (Haiti)

In December 2021, UNESCO inscribed Joumou Soup on its Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity, recognising it as a powerful symbol of Haitian independence and resilience.

Joumou, a rich pumpkin or squash soup made with vegetables, meat, pasta, and spices, holds deep historical significance in Haiti. This humble food item was once a delicacy reserved exclusively for French colonial slave owners, forbidden to the enslaved African Haitians who cultivated the main ingredient—giraumon, a native Caribbean pumpkin variant. Following Haiti’s victorious revolution and declaration of independence on January 1, 1804, Haitians transformed soup joumou into a celebratory dish that expressed their newfound freedom and dignity.

Every New Year’s Day, which coincides with Haitian Independence Day, Haitians at home and across the diaspora prepare and share this soup as the first meal of the year. The food tradition serves not only as a feast but also as a social ritual that strengthens family bonds and communal ties. The preparation of joumou is a collaborative process involving women managing cooking activities, children helping with ingredients, artisans creating cooking utensils, and farmers harvesting produce. The soup is often consumed throughout New Year’s Day and into Ancestors’ Day on January 2, honouring Haitian revolutionary heroes.

Beyond its nutritional richness, joumou embodies the spirit of resistance, emancipation, and cultural pride. It acts as a “bowl of freedom” connecting generations and communities, reminding Haitians of their resilient past and shared identity.

Nsima (Malawi)

Nsima, recognised by UNESCO in 2017 as an important element of Malawi’s Intangible Cultural Heritage, is more than a staple food—it is a powerful emblem of communal identity and tradition

At its core, Nsima is a thick, smooth maize porridge that serves as the foundation of Malawian meals. Maize, introduced to Africa centuries ago, quickly became a dietary cornerstone due to its adaptability and nutritional value. In Malawi, Nsima is made daily by boiling maize flour with water until it reaches a firm, dough-like consistency that is shaped by hand or spooned onto a plate.

The preparation of Nsima is an intricate, communal process involving several steps that ensure quality and tradition are upheld. The maize may be ground by hand using traditional milling techniques, often involving women and younger family members working together. Beyond just cooking, the act of preparing Nsima fosters communal ties and intergenerational knowledge transfer, with elders passing culinary skills and mealtime etiquette to children.

Mealtime customs surrounding Nsima are highly ritualistic, reflecting respect, hospitality, and social cohesion. It is typically served alongside relishes made from vegetables, legumes, or meat, reflecting seasonal and regional diversity. Eating Nsima often involves sharing from a common plate, symbolising unity and collective nourishment.

An interesting aspect of Nsima’s cultural role is its place in education and socialisation. Knowledge of Nsima preparation and its social significance is imparted informally within families and more formally within schools, reinforcing its status as a cultural pillar and a daily ritual that shapes Malawian identity.

Through UNESCO’s recognition, Nsima’s legacy is safeguarded, ensuring that its culinary techniques, social meaning, and communal practices continue to thrive amid modernisation, preserving an essential part of Malawi’s cultural heritage for future generations.

Ceremonial Keşkek (Turkey)

In 2011, UNESCO inscribed the Ceremonial Keşkek tradition on its Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity, recognising it as a vital cultural practice that fosters community bonding and social harmony across rural Turkey.

Keşkek is a hearty, slow-cooked stew made from wheat and meat—commonly chicken or lamb. It is traditionally prepared for significant life events such as weddings, circumcisions, religious holidays, and other communal celebrations. The wheat is first washed with prayers the day before cooking, then hulled in a large stone mortar by two to four persons working rhythmically with wooden gavels, often accompanied by music from the davul drum and zurna pipe.

Cooking usually takes place outdoors in large cauldrons, with wheat, meat, onions, spices, water, and oil simmering overnight. As the stew thickens near serving time, robust village youth “beat” the keşkek vigorously with wooden mallets, coordinated to rhythmic music and communal cheering. This collective pounding is a highlight of the ceremony, symbolising not just the physical preparation but also the forging of social unity and harmony.

Men and women collaborate in the various stages of preparation, and the event includes entertainment such as music, plays, and performances, transforming the cooking process into a festive communal occasion. Keşkek’s preparation and consumption thus extend beyond mere sustenance; it is an integral part of rural social life, embodying shared heritage, mutual support, and celebration.

Oshi Palav (Tajikistan/Uzbekistan)

Oshi palav, also known as pilaf, is a celebrated traditional rice-based dish emblematic of Tajikistan and broader Central Asian culture. It was inscribed on the UNESCO Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity in 2016, following Tajikistan’s nomination. This dish is revered as the “king of meals,” highlighting its central role in social life, including weddings, religious festivities, holidays, and significant communal gatherings.

Oshi palav’s origins are ancient, potentially dating back to the Sogdian and Bactrian civilisations around the 2nd century BCE. These people contributed to the development of Central Asia’s rich agricultural and culinary traditions. The dish is a complex preparation featuring rice, meat (often lamb or beef), vegetables such as carrots and onions, and a distinctive blend of spices. Each community often adds its own variations, reflecting local tastes and ingredients.

It is often cooked outdoors or in communal settings where groups of men or women work together, accompanied by music and singing. The process is both culinary and cultural, serving as a social ritual of hospitality and friendship. The significance of the dish is echoed in local sayings like “No Osh, no acquaintance,” meaning sharing a meal of oshi palav symbolises respect and social connection lasting up to 40 years.

There are reportedly up to 200 varieties of oshi palav, each showcasing unique local twists in ingredients and preparation styles, underscoring the dish’s versatility and deep cultural embedding across Central Asia. Culinary knowledge and techniques are traditionally passed down intergenerationally, both within families and through apprentice programs where mastery is ceremonially recognised.

Lavash Bread (Armenia)

Lavash, a soft and thin flatbread, holds a cherished place in Armenian culture and culinary tradition. Officially inscribed by UNESCO as an Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity, this bread extends beyond mere sustenance to embody a vital social and cultural practice deeply rooted in Armenia and the surrounding West Asian region.

Lavash has been a staple in Armenian households for generations, its origins tracing back thousands of years as a fundamental bread of the region. Traditionally, lavash is baked in a tonir—a cylindrical clay oven buried in the earth—where the dough is skillfully slapped onto the hot walls to bake quickly, creating a distinct texture that is soft yet sturdy. The entire process is largely a communal one, historically dominated by women who gather to prepare the dough, bake the bread, and share stories and songs, thus strengthening community bonds and passing down culinary skills from one generation to the next.

The making of lavash is considered a social event as much as a culinary one, involving cooperation, coordination, and dialogue among families and neighbours. This intergenerational exchange ensures the continuity of traditional techniques and reinforces cultural identity through shared heritage.

Lavash holds symbolic and ritual significance beyond daily meals. It is traditionally used in important life events such as cradling newborn babies, symbolising protection and warmth. During Armenian weddings, lavash is often wrapped around the bride’s shoulders as a blessing for prosperity and health, reflecting its sacred role in life-cycle ceremonies. Furthermore, lavash is versatile—used for making wraps, accompanying stews, or eaten fresh—making it a culinary cornerstone with profound cultural resonance.

Couscous (Morocco)

In December 2020, a joint nomination by Algeria, Morocco, Tunisia, and Mauritania led to the inscription of the knowledge, know-how, and practices pertaining to the production and consumption of couscous on UNESCO’s Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity. This marked a rare moment of unity in the Maghreb region, emphasizing couscous as a shared cultural treasure despite the countries’ political and historical differences.

Couscous is a staple dietary element across the Maghreb, originally linked to Berber heritage. The dish consists of semolina grains—made from wheat, barley, maize, millet, or sorghum—that are moistened, rolled into tiny granules, and steamed multiple times to achieve a light, fluffy texture. Couscous is traditionally served with richly spiced stews of meat, fish, chickpeas, and vegetables, making it central to life-cycle celebrations, village feasts, and other communal and religious events.

The entire process involves a wide cultural ecosystem: farmers grow the cereals, millers prepare the semolina, artisans craft cooking utensils, and especially women play a fundamental role in rolling, steaming, and serving the couscous. Preparation techniques, songs, gestures, oral expressions, and ritual organization related to couscous are passed down orally across generations, reinforcing social cohesion and cultural identity.

The joint UNESCO nomination was notable as an example of cultural cooperation among the four nations, underscoring couscous as a unifying symbol amid regional culinary rivalries. While each country’s style has unique touches, couscous represents the ethos of community life in the Maghreb. The shared pride in this dish helps bridge divides, with its presence felt at both everyday family meals and major cultural events. It is so beloved that Moroccan chef Hicham Hazzoum remarked that couscous is a weekly staple, beloved even by children.

Tom Yum Soup (Thailand)

In 2024, Tom Yum Soup was inscribed on UNESCO’s Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity, recognising it as an iconic symbol of Thai culinary tradition and cultural identity.

Tom Yum is a classic hot and sour soup that epitomises the vibrant flavour profile central to Thai cuisine. Traditionally made with fresh ingredients like lemongrass, kaffir lime leaves, galangal, fresh chillies, lime juice, and proteins such as shrimp (Tom Yum Goong), the soup offers a harmonious balance of spicy, sour, salty, and sweet tastes. Originating from central Thailand, Tom Yum has long been a staple in Thai households and street food culture, served both as an everyday comfort food and a dish for special occasions.

The preparation of Tom Yum is steeped in tradition, emphasising fresh herbs and natural ingredients sourced locally. The soup’s depth of flavour is crafted through the precise layering of aromatics and the delicate timing of cooking ingredients to preserve their distinct tastes and textures. It is often enjoyed communally, reflecting Thai values of sharing and hospitality.

Peruvian Ceviche

In December 2023, UNESCO inscribed the practices and meanings associated with the preparation and consumption of ceviche on its Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity, officially recognizing this iconic Peruvian dish as a vital expression of the country’s traditional cuisine.

Ceviche is a celebrated dish of raw fish marinated in fresh citrus juice—typically lime or lemon—and seasoned with local ingredients such as onions, chili peppers, and salt. This “cooking” by acid is a hallmark of the dish, which originated in Peru’s coastal fishing communities. Ceviche embodies a fusion of Indigenous culinary knowledge—dating back to ancient civilizations like the Caral, Moche, and Chimú, who consumed fish, salt, and hot peppers—and the influences introduced during the Spanish colonial period.

The preparation and consumption of ceviche is much more than a recipe; it represents a cultural system involving artisanal fishing, farming of key ingredients like citrus and chili, cooking techniques passed down through families, and communal sharing. The dish is found throughout Peru with regional variations that highlight the nation’s rich biodiversity and cultural diversity. Ceviche is commonly enjoyed in cevicherías (specialized eateries) where traditional female cooks, or picanteras, are highly respected.

UNESCO noted that ceviche’s inscription promotes sustainable food practices, respect for marine and agricultural resources, social cohesion, and economic development linked to food heritage.

Peru celebrates National Ceviche Day every June 28, honoring the dish’s cultural importance and culinary diversity across regions. Ceviche remains a symbol of national pride and an emblem of Peru’s gastronomic revolution that has gained wide international acclaim.

Read More: Latest